Python - Functions

Overview

Questions:Objectives:

How do I write functions in Python?

What is a function?

What do they look like?

Fill in the missing part of a function

Requirements:

Understand the structure of a “function” in order to be able to construct their own functions and predict which functions will not work.

- Foundations of Data Science

- Python - Math: tutorial hands-on

Time estimation: 30 minutesLevel: Introductory IntroductorySupporting Materials:Last modification: Apr 25, 2022

Best viewed in a Jupyter Notebook

This tutorial is best viewed in a Jupyter notebook! You can load this notebook one of the following ways

Launching the notebook in Jupyter in Galaxy

- Instructions to Launch JupyterLab

- Open a Terminal in JupyterLab with File -> New -> Terminal

- Run

wget https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/python-functions/data-science-python-functions.ipynb- Select the notebook that appears in the list of files on the left.

Downloading the notebook

- Right click one of these links: Jupyter Notebook (With Solutions), Jupyter Notebook (Without Solutions)

- Save Link As..

Functions are the basic unit of all work in Python! Absolutely everything you do uses functions. Conceptually, functions are super simple. Just like in maths, they take an input, do some transformation, and return an output. As an example, f(x) = x + 2 is a function that calculates whatever value you request, plus two. But functions are foundational, so, you should understand them well before moving on.

Agenda

In this tutorial, we will cover:

What is a Function

Functions are a way to re-use some computation you want to do, multiple times. If you don’t have a function, you need to re-write the calculation every time, so we use functions to collect those statements and make them easy to re-run. Additionally they let us “parameterise” some computation. Instead of computing the same value every time, we can template it out, we can re-run the computation with new inputs, and see new results.

code-in Math

# Define our function f(x) = 3 * x # Compute some value f(3) # is 9code-out Python

# Define our function def f(x): return 3 * x # Compute some value f(3)

We’ve talked about mathematical functions before, but now we’ll talk about more programing-related functions

Create Functions

Human beings can only keep a few items in working memory at a time. Breaking down larger/more complicated pieces of code in functions helps in understanding and using it. A function can be re-used. Write one time, use many times. (Known as staying Don’t Repeat Yourself (DRY) in the industry.)

Knowing what Americans mean when they talk about temperatures and weather can be difficult, but we can wrap the temperature conversion calculation (\(^{\circ}\text{C} = (^{\circ}\text{F} - 32) * \dfrac{5}{9}\)) up as a function that we can easily re-use.

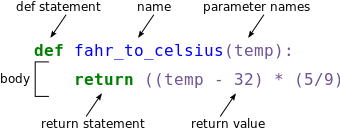

def fahr_to_celsius(temp):

return ((temp - 32) * (5/9))

The function definition opens with the keyword def followed by the name of the function fahr_to_celsius and a parenthesized list of parameter names temp. The body of the function — the statements that are executed when it runs — is indented below the definition line. The body concludes with a return keyword followed by the return value.

When we call the function, the values we pass to it are assigned to those variables so that we can use them inside the function. Inside the function, we use a return statement to send a result back to whoever asked for it.

Let’s try running our function.

fahr_to_celsius(32)

print(f"freezing point of water: {fahr_to_celsius(32)}C")

print(f"boiling point of water: {fahr_to_celsius(212)}C")

tip Formatting Strings

There are several ways to print out a few values in python. We’d recommend you to use

f-stringsas it’s the cleanest and most modern way to do it.

f-strings start with anf(very descriptive name eh?). Within the text between the single or double quotes ('/") you can use curly braces to refer to variables or python code which will be placed there in the string.a = 10 b = f"Here is the value of a: {a}" print(b) print(f"Here is the value of a: {5 + 5}") print(f"Here is the value of a: {function_that_returns_10()}")All of those would print out

Here is the value of a: 10.f-strings can be a lot fancier for formatting decimal places, but we don’t need that for now. Just know:

- Start with an

f- Use braces to use the value of a variable, a function, or some python expression.

We’ve successfully called the function that we defined, and we have access to the value that we returned.

Now that we’ve seen how to turn Fahrenheit into Celsius, we can also write the function to turn Celsius into Kelvin:

def celsius_to_kelvin(temp_c):

return temp_c + 273.15

print(f'freezing point of water in Kelvin: {celsius_to_kelvin(0.)}')

tip Tip: What is

0.That’s a float! A

.in a number makes it a float, rather than an integer.

What about converting Fahrenheit to Kelvin? We could write out both formulae, but we don’t need to. Instead, we can compose the two functions we have already created:

def fahr_to_kelvin(temp_f):

temp_c = fahr_to_celsius(temp_f)

temp_k = celsius_to_kelvin(temp_c)

return temp_k

print(f'boiling point of water in Kelvin: {fahr_to_kelvin(212.0)}')

This is our first taste of how larger programs are built: we define basic operations, then combine them in ever-larger chunks to get the effect we want. Real-life functions will usually be larger than the ones shown here — typically half a dozen to a few dozen lines — but they shouldn’t ever be much longer than that, or the next person who reads it won’t be able to understand what’s going on.

Documentation

Documenting your code is extremely, extremely, extremely important to do. We all forget what we’re doing, it’s only normal, so documenting what you’re doing is key to being able to restart work later.

def fahr_to_kelvin(temp_f):

"""

Converts a temperature from Fahrenheit to Kelvin

temp_f: the temperature in Fahrenheit

returns the temperature in Celsius

"""

temp_c = fahr_to_celsius(temp_f)

temp_k = celsius_to_kelvin(temp_c)

return temp_k

print(f'boiling point of water in Kelvin: {fahr_to_kelvin(212.0)}')

For a function this small, with such a descriptive name (fahr_to_kelvin) it feels quite obvious what the function should do, what inputs it takes, what outputs it produces. However

question Question: Converting statements to functions

A lot of what you’ll do in programing is to turn a procedure that you want to do, into statements and a function.

Fill in the missing portions of this function, two average numbers. Then use it to find the average of 32326 and 631

solution Solution

def average2(a, b): c = (a + b) / 2 return c

# Test out solutions here!

def average2(a, b):

c =

return c

print(average2(32326, 631))

question Question: A more complicated example

The formula for a 90° triangle can be expressed as: \(c = \sqrt{a^2 + b^2}\)

- Write a function which takes

aandb, and calculatesc- Name this function “pythagorus”

- Remember to import math, if you haven’t already

solution Solution

def pythagorus(a, b): c = math.sqrt(math.pow(a, 2) + math.pow(b, 2)) return c

# Test out solutions here!

print(pythagorus(1234, 4321)) # Should return 4493.750883170984

Variable Scope

In composing our temperature conversion functions, we created variables inside of those functions, temp, temp_c, temp_f, and temp_k. We refer to these variables as local variables because they no longer exist once the function is done executing. If we try to access their values outside of the function, we will encounter an error:

print(f'Again, temperature in Kelvin was: {temp_k}')

If you want to reuse the temperature in Kelvin after you have calculated it with fahr_to_kelvin, you can store the result of the function call in a variable:

temp_kelvin = fahr_to_kelvin(212.0)

print(f'temperature in Kelvin was: {temp_kelvin}')

Watch out for scope issues:

- Variables created inside a function will stay inside the function

- Variables created outside of the function can be accessible inside the function, but you should not do this!

- Ensure that variables are properly scoped will prevent later errors when working with modules or testing big projects.

a = 1

b = 2.0

# Location 1

def some_generic_computation(x, y):

c = x + y

d = x * y

e = c / d

# Location 2

return e

# Location 3

question Question: Scope

Given the above code, which variables are accessible at Locations 1, 2, and 3?

solution Solution

- a, b

- a and b are there but you shouldn’t use these. x, y, c, d, e are also accessible.

- a, b.

Defining Default parameters

If we usually want a function to work one way, but occasionally need it to do something else, we can allow people to pass a parameter when they need to but provide a default to make the normal case easier. The example below shows how Python matches values to parameters:

def display(a=1, b=2, c=3):

print(f'a: {a}, b: {b}, c: {c}')

# no parameters:

display()

# one parameter:

display(55)

# two parameters:

display(55, 66)

As this example shows, parameters are matched up from left to right, and any that haven’t been given a value explicitly get their default value. We can override this behavior by naming the value as we pass it in:

# only setting the value of c

display(c=77)

question Exercise: Signing a message

Let’s test out a default argument. Imagine you are printing out a message, and at the bottom it should have a signature.

Inputs:

message: a variable that is always provided to the function, it has no default.signature: a variable that can be optionally provided, it should have a default like your name.You can accomplish this with three print statements:

- Print the message

- Print nothing (i.e.

print())- Print a signature variable.

solution Solution

def myFunction(message, signature="Your name"): print(message) print() print(signature)

# Test things out here!

def myFunction # Fix this function!

# Here are some test cases, for you to check if your function works!

myFunction('This is a message')

myFunction('This is a message', signature='Jane Doe')

Key points

Functions are foundational in Python

Everything you do will require functions

Frequently Asked Questions

Have questions about this tutorial? Check out the FAQ page for the Foundations of Data Science topic to see if your question is listed there. If not, please ask your question on the GTN Gitter Channel or the Galaxy Help ForumGlossary

- DRY

- Don't Repeat Yourself

Feedback

Did you use this material as an instructor? Feel free to give us feedback on how it went.

Did you use this material as a learner or student? Click the form below to leave feedback.

Citing this Tutorial

- The Carpentries, Helena Rasche, Donny Vrins, Bazante Sanders, 2022 Python - Functions (Galaxy Training Materials). https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/python-functions/tutorial.html Online; accessed TODAY

- Batut et al., 2018 Community-Driven Data Analysis Training for Biology Cell Systems 10.1016/j.cels.2018.05.012

details BibTeX

@misc{data-science-python-functions, author = "The Carpentries and Helena Rasche and Donny Vrins and Bazante Sanders", title = "Python - Functions (Galaxy Training Materials)", year = "2022", month = "04", day = "25" url = "\url{https://training.galaxyproject.org/training-material/topics/data-science/tutorials/python-functions/tutorial.html}", note = "[Online; accessed TODAY]" } @article{Batut_2018, doi = {10.1016/j.cels.2018.05.012}, url = {https://doi.org/10.1016%2Fj.cels.2018.05.012}, year = 2018, month = {jun}, publisher = {Elsevier {BV}}, volume = {6}, number = {6}, pages = {752--758.e1}, author = {B{\'{e}}r{\'{e}}nice Batut and Saskia Hiltemann and Andrea Bagnacani and Dannon Baker and Vivek Bhardwaj and Clemens Blank and Anthony Bretaudeau and Loraine Brillet-Gu{\'{e}}guen and Martin {\v{C}}ech and John Chilton and Dave Clements and Olivia Doppelt-Azeroual and Anika Erxleben and Mallory Ann Freeberg and Simon Gladman and Youri Hoogstrate and Hans-Rudolf Hotz and Torsten Houwaart and Pratik Jagtap and Delphine Larivi{\`{e}}re and Gildas Le Corguill{\'{e}} and Thomas Manke and Fabien Mareuil and Fidel Ram{\'{\i}}rez and Devon Ryan and Florian Christoph Sigloch and Nicola Soranzo and Joachim Wolff and Pavankumar Videm and Markus Wolfien and Aisanjiang Wubuli and Dilmurat Yusuf and James Taylor and Rolf Backofen and Anton Nekrutenko and Björn Grüning}, title = {Community-Driven Data Analysis Training for Biology}, journal = {Cell Systems} }

Congratulations on successfully completing this tutorial!

Do you want to extend your knowledge? Follow one of our recommended follow-up trainings:

Questions:

Questions: