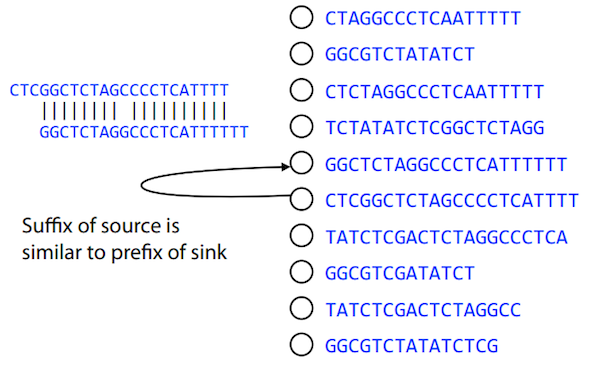

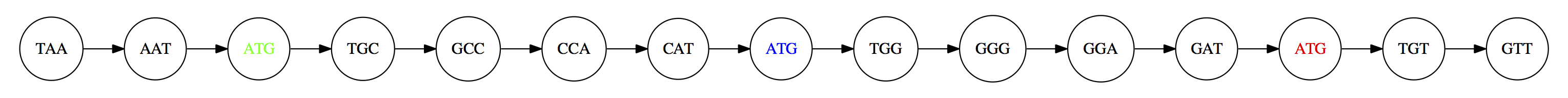

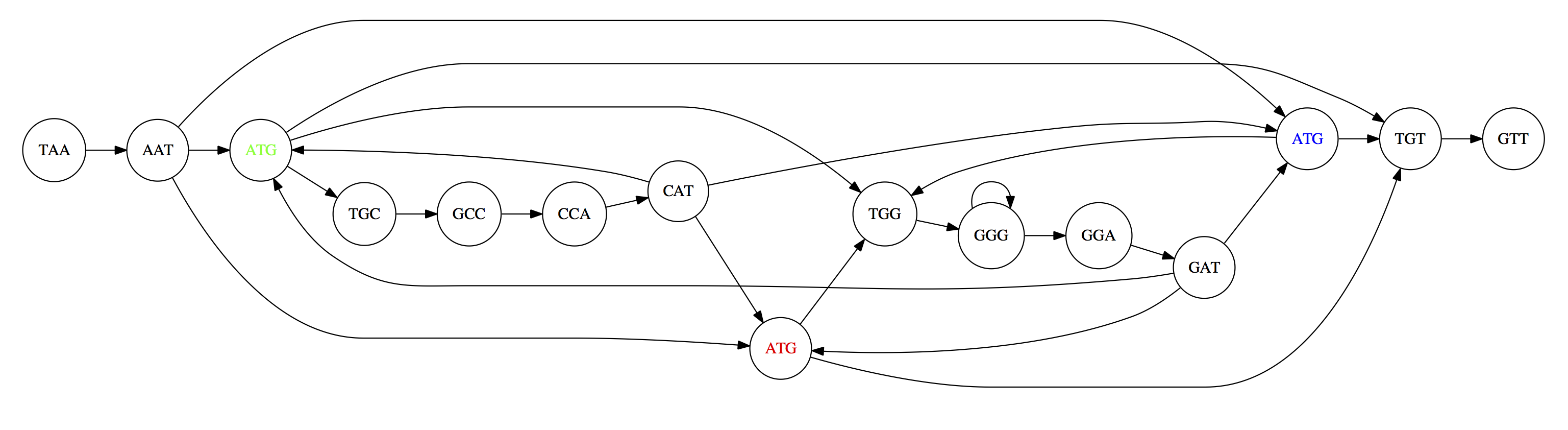

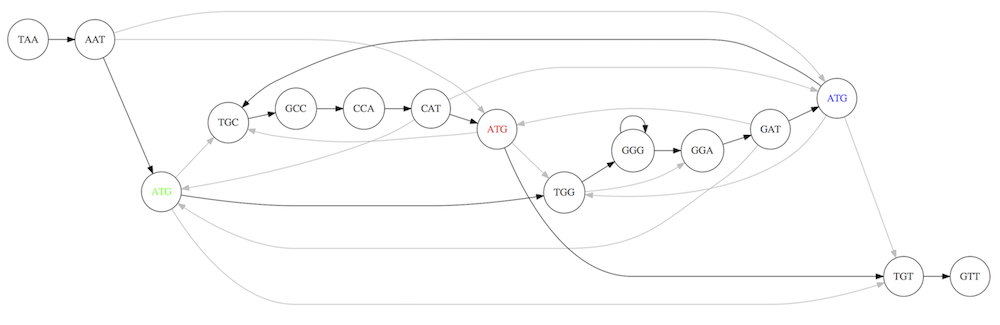

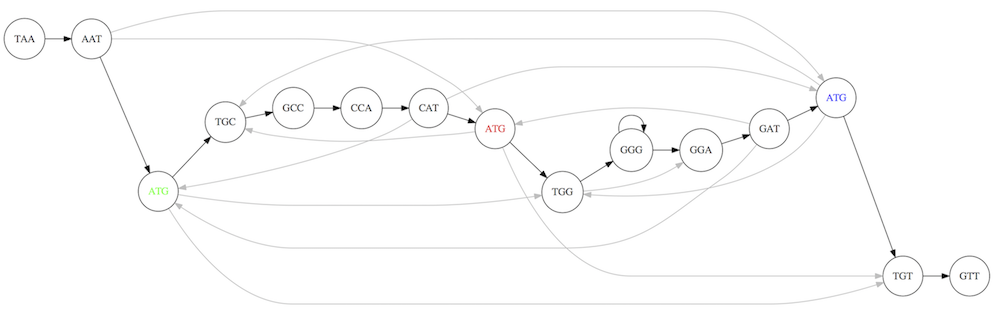

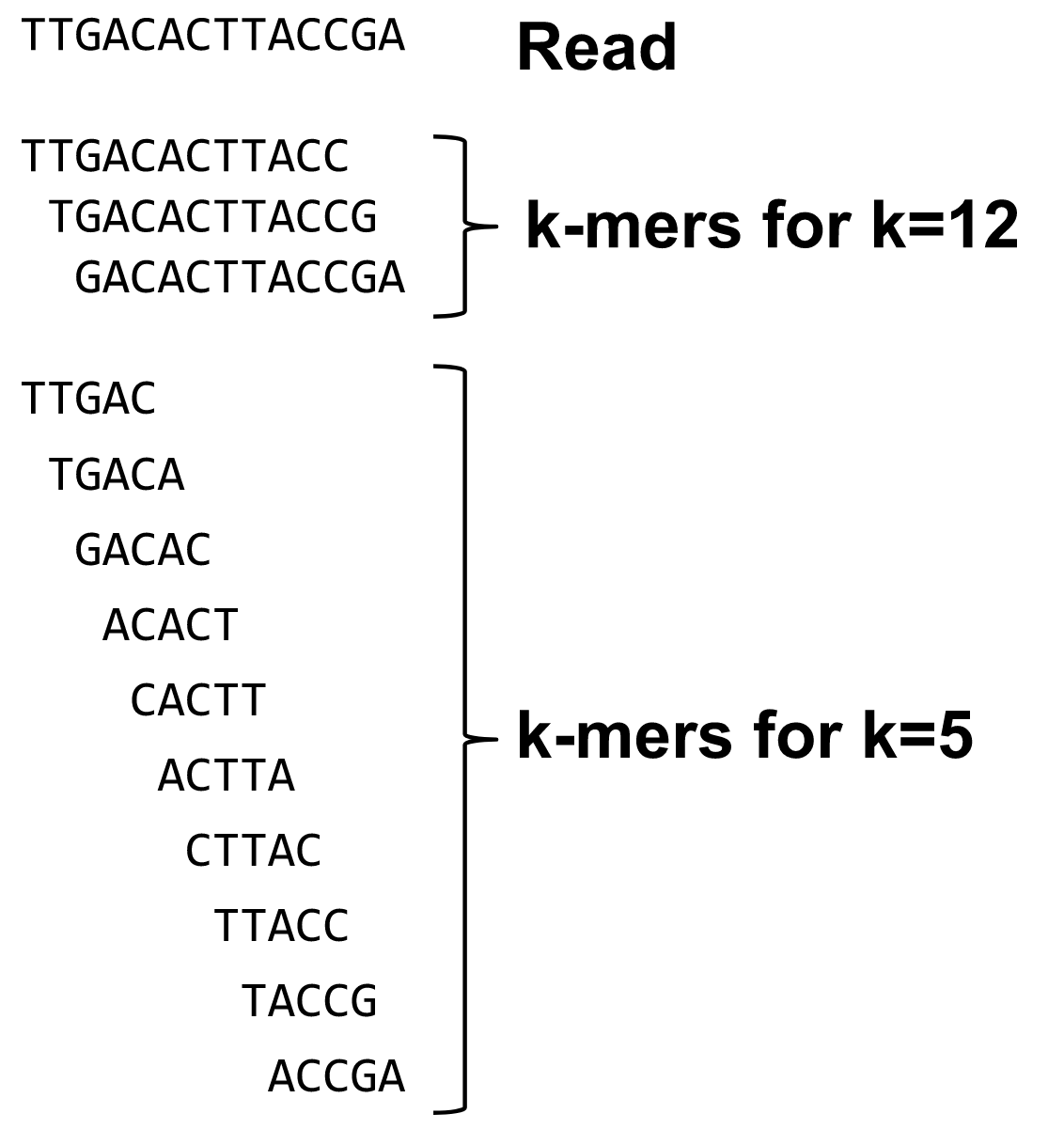

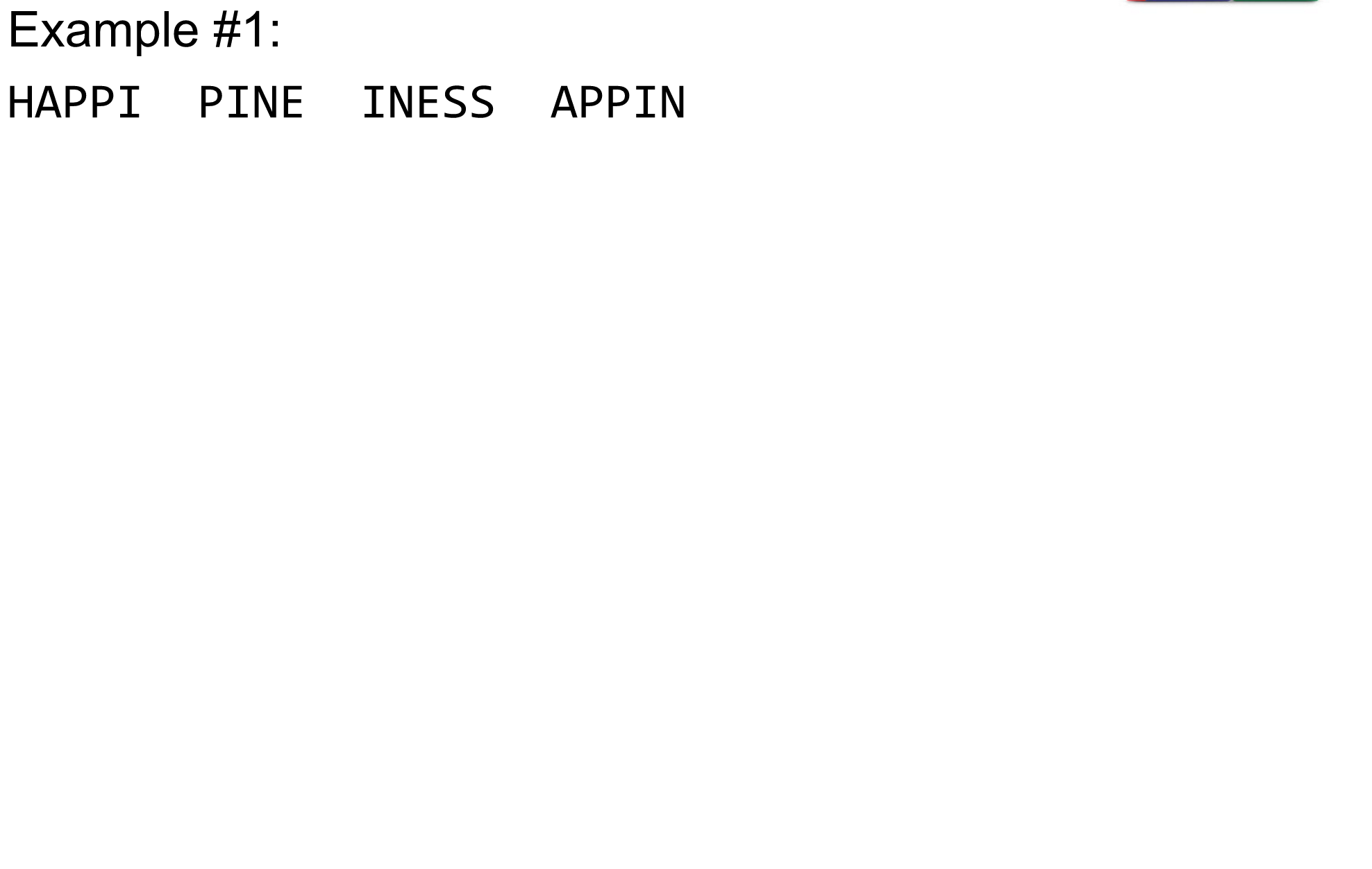

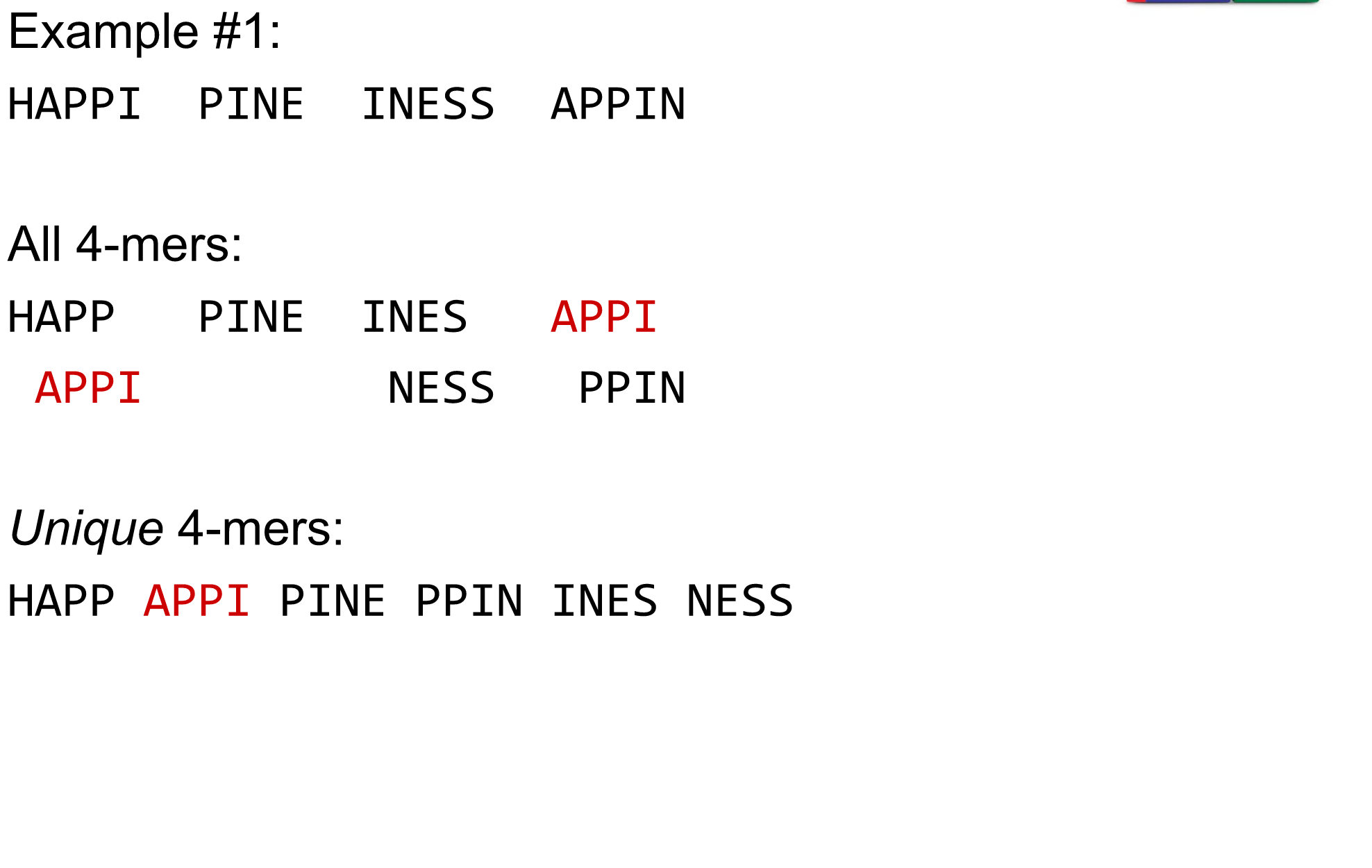

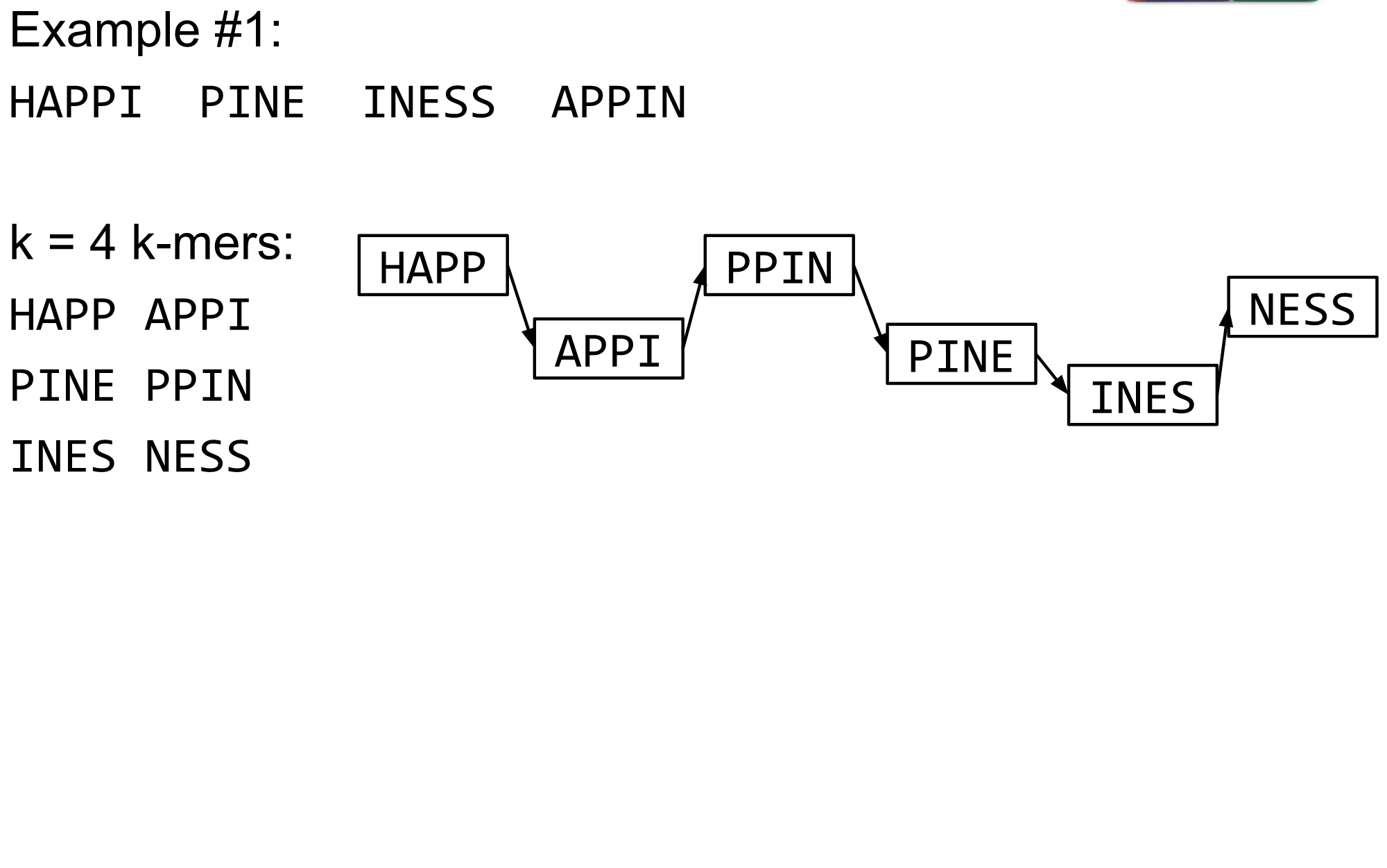

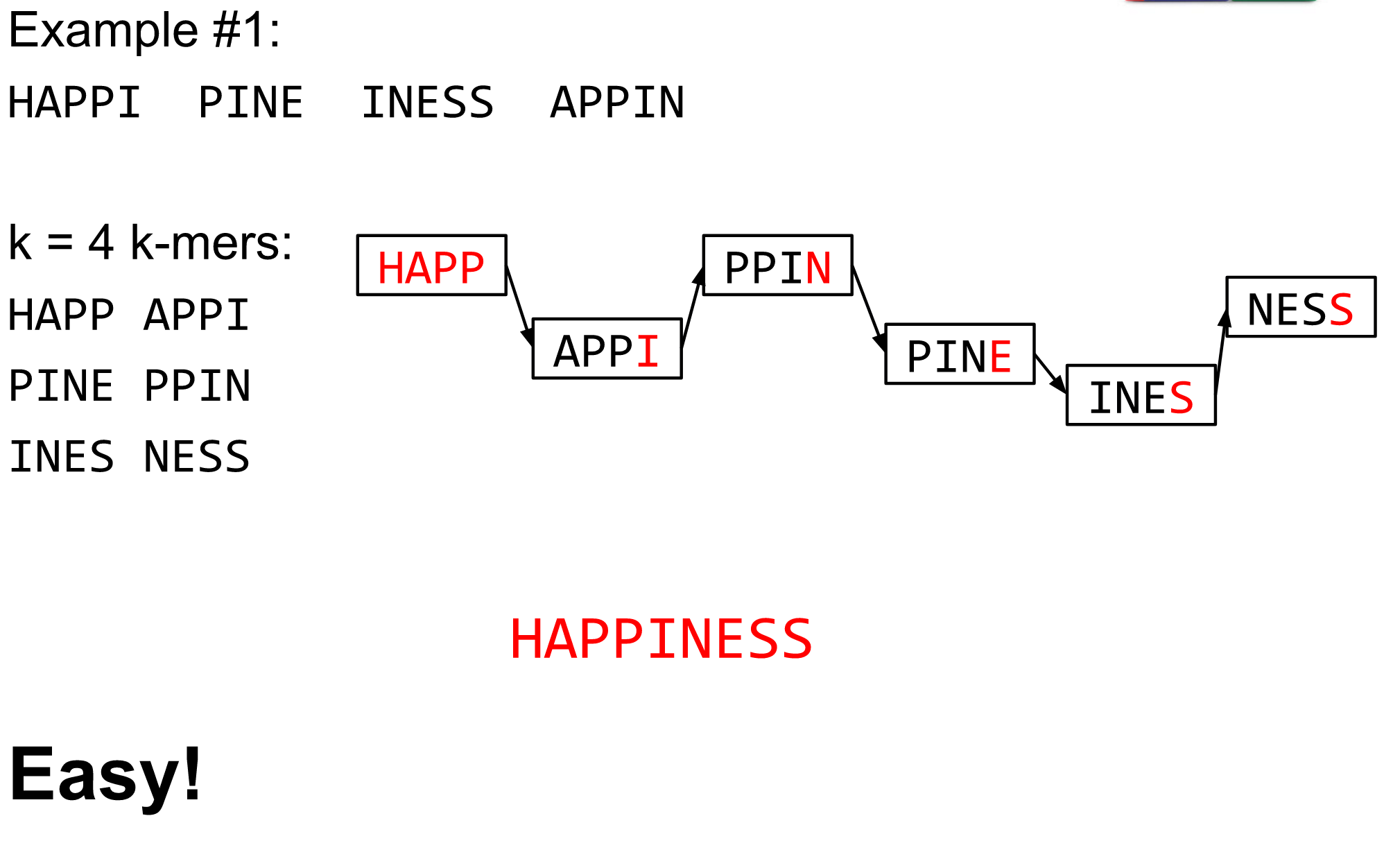

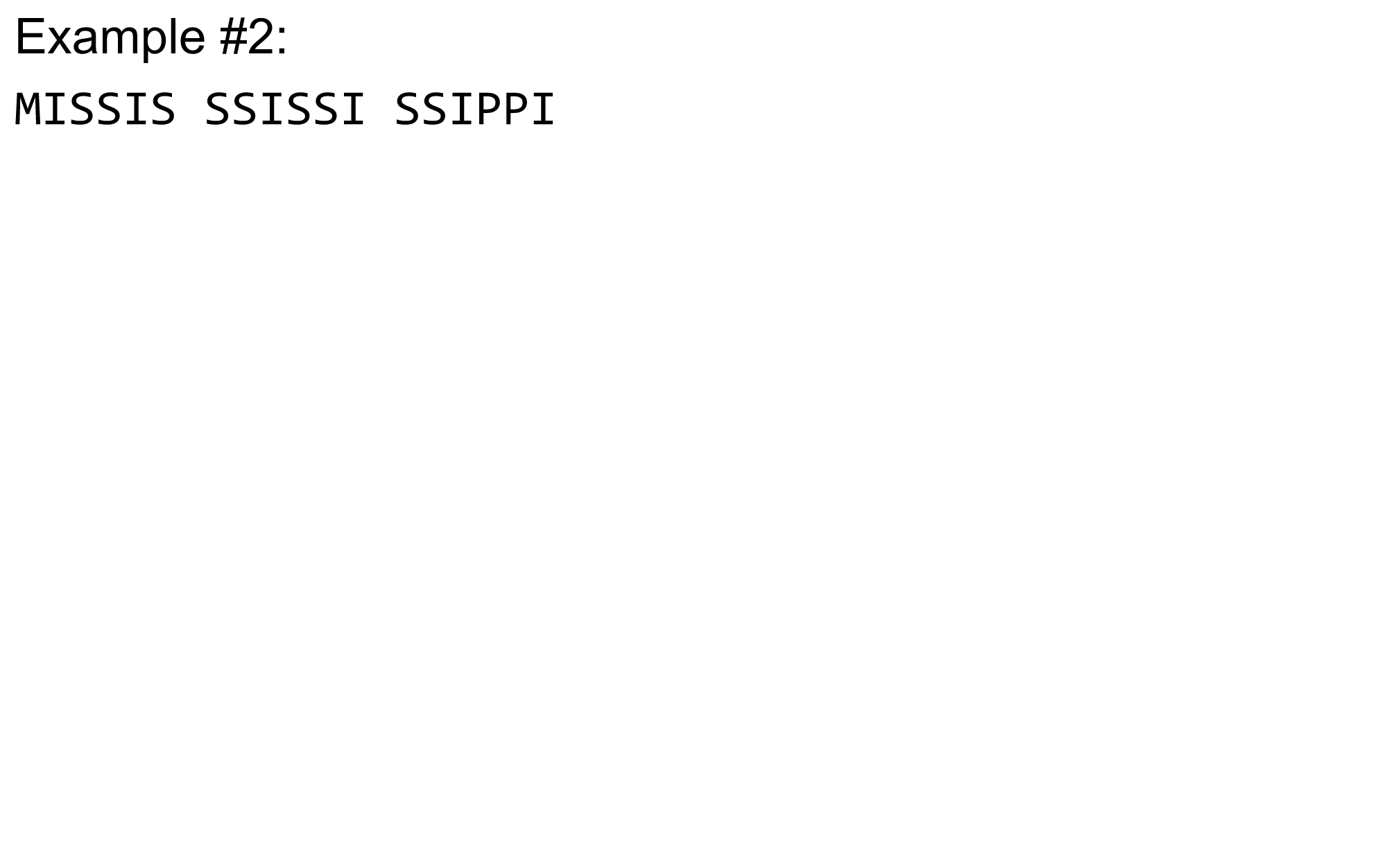

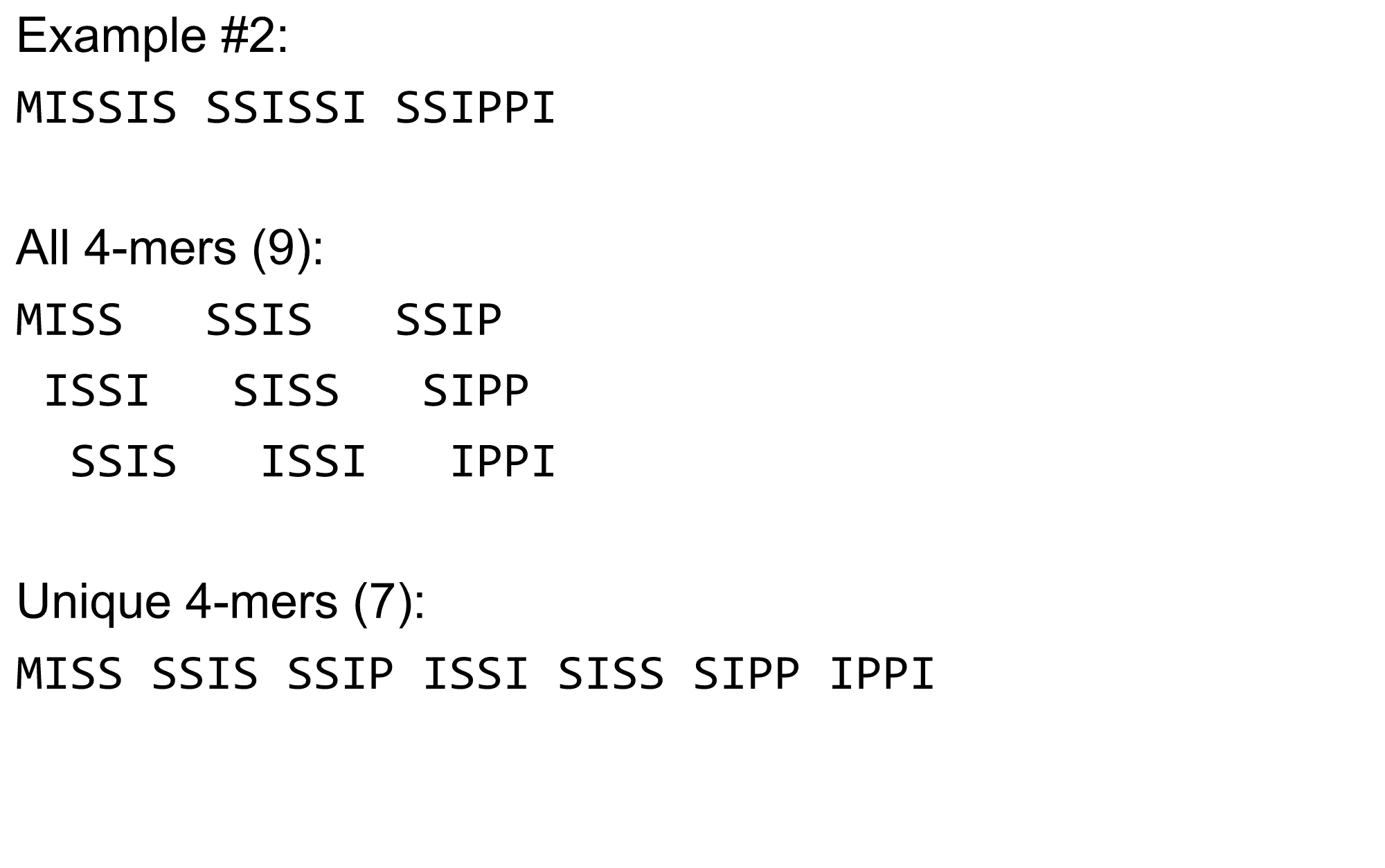

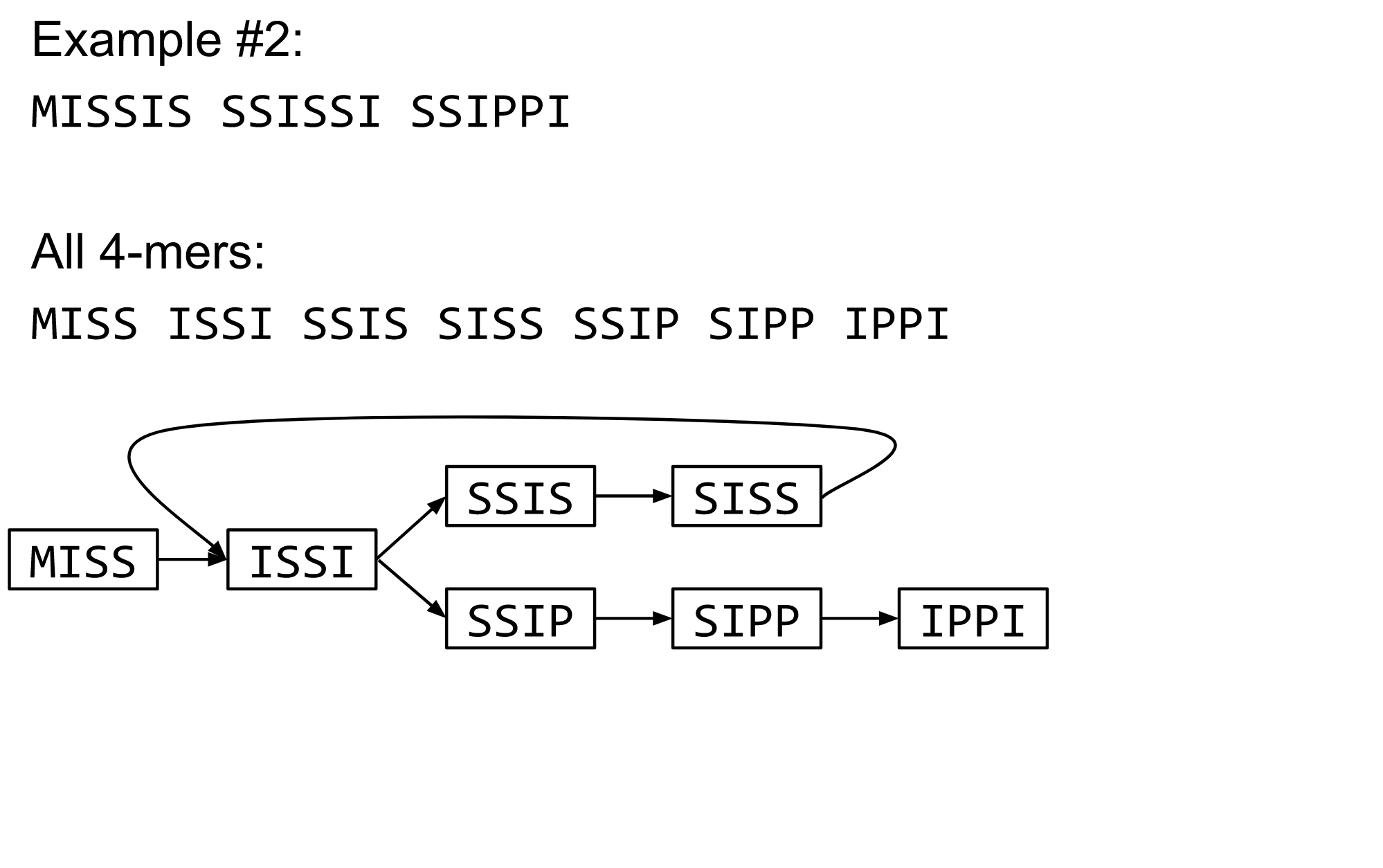

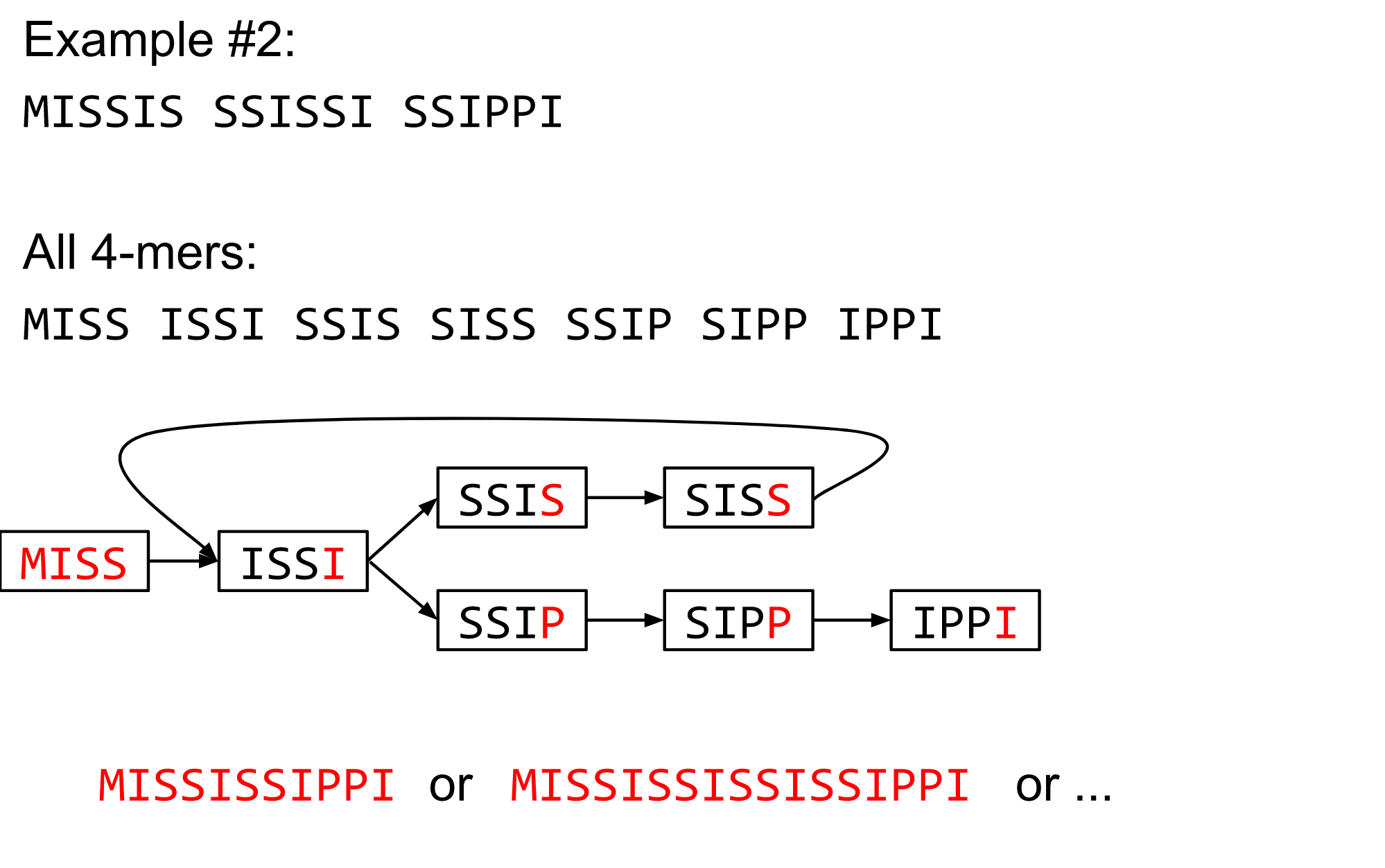

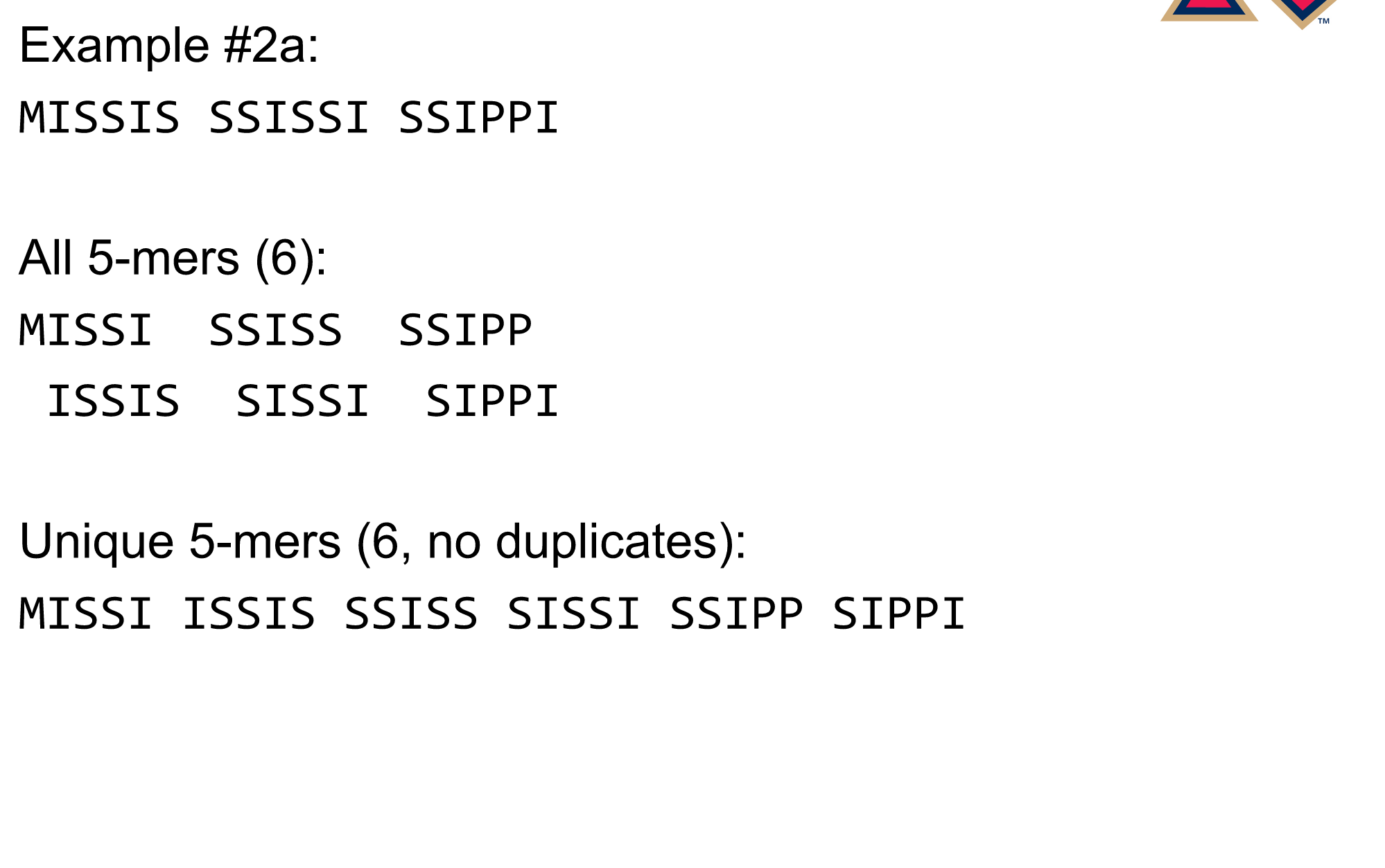

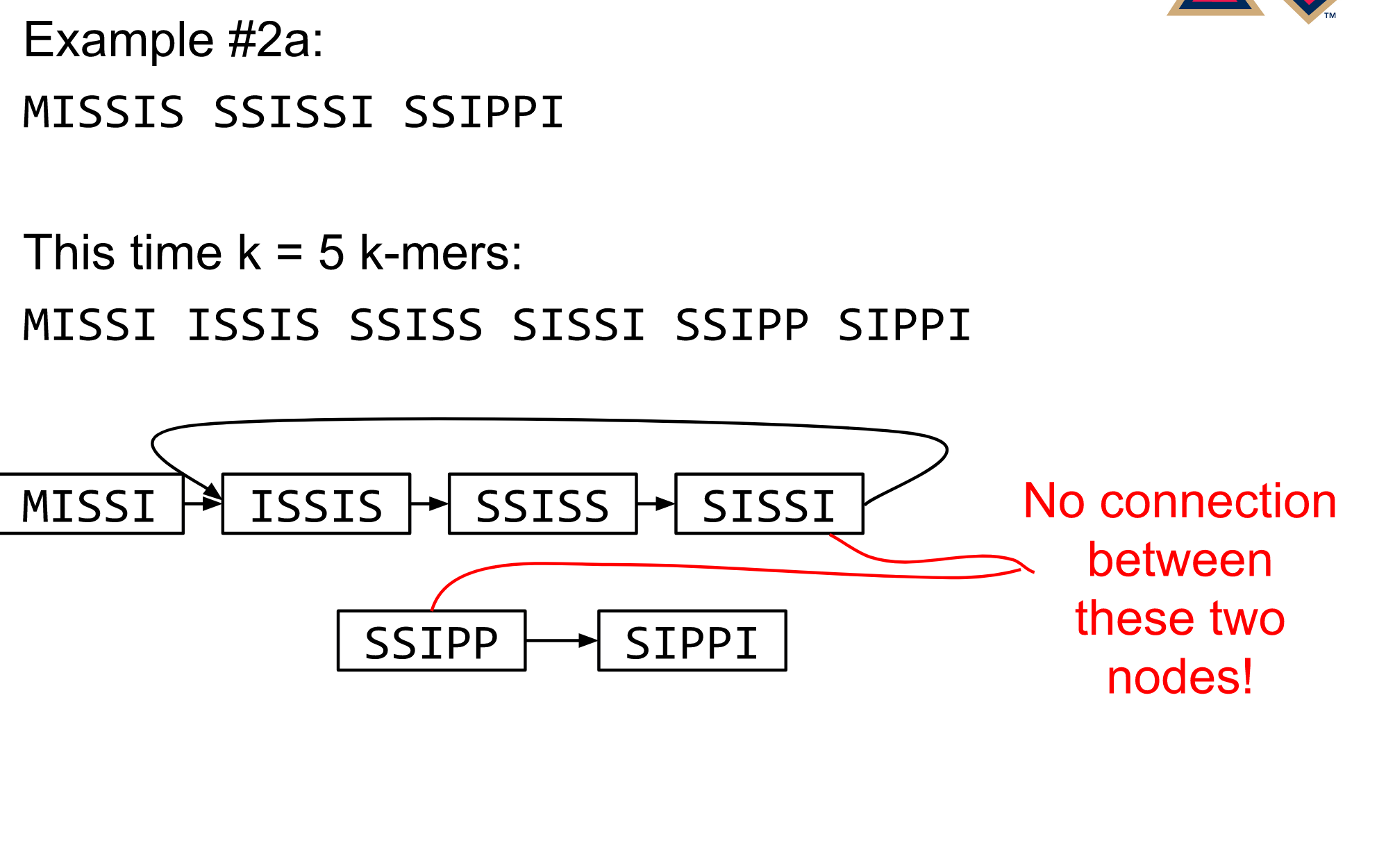

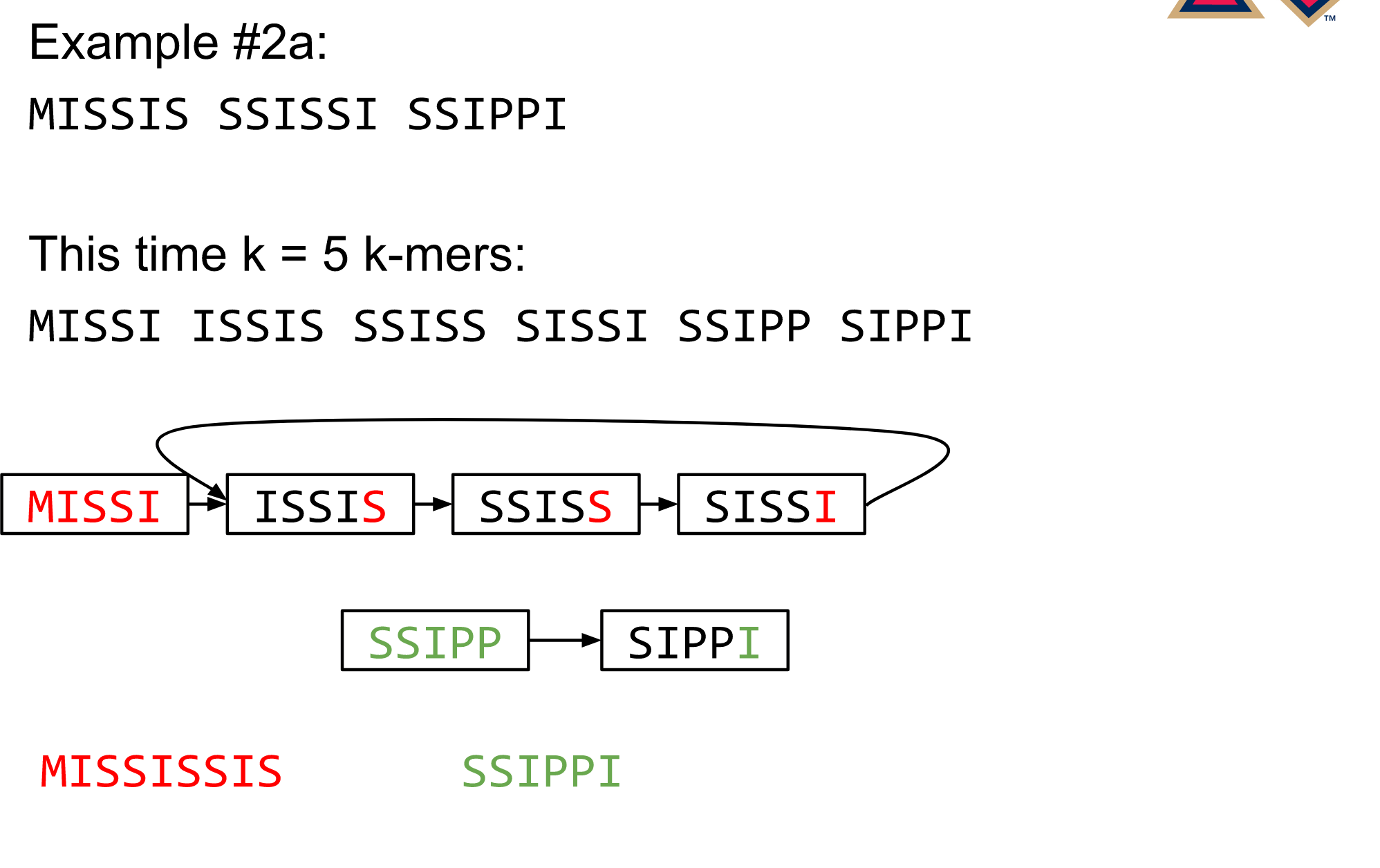

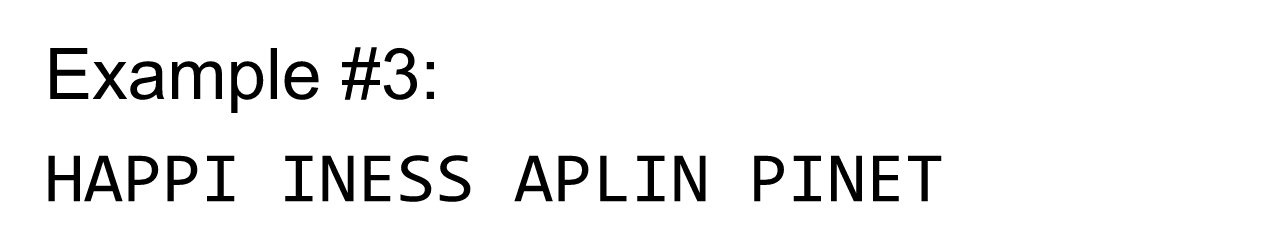

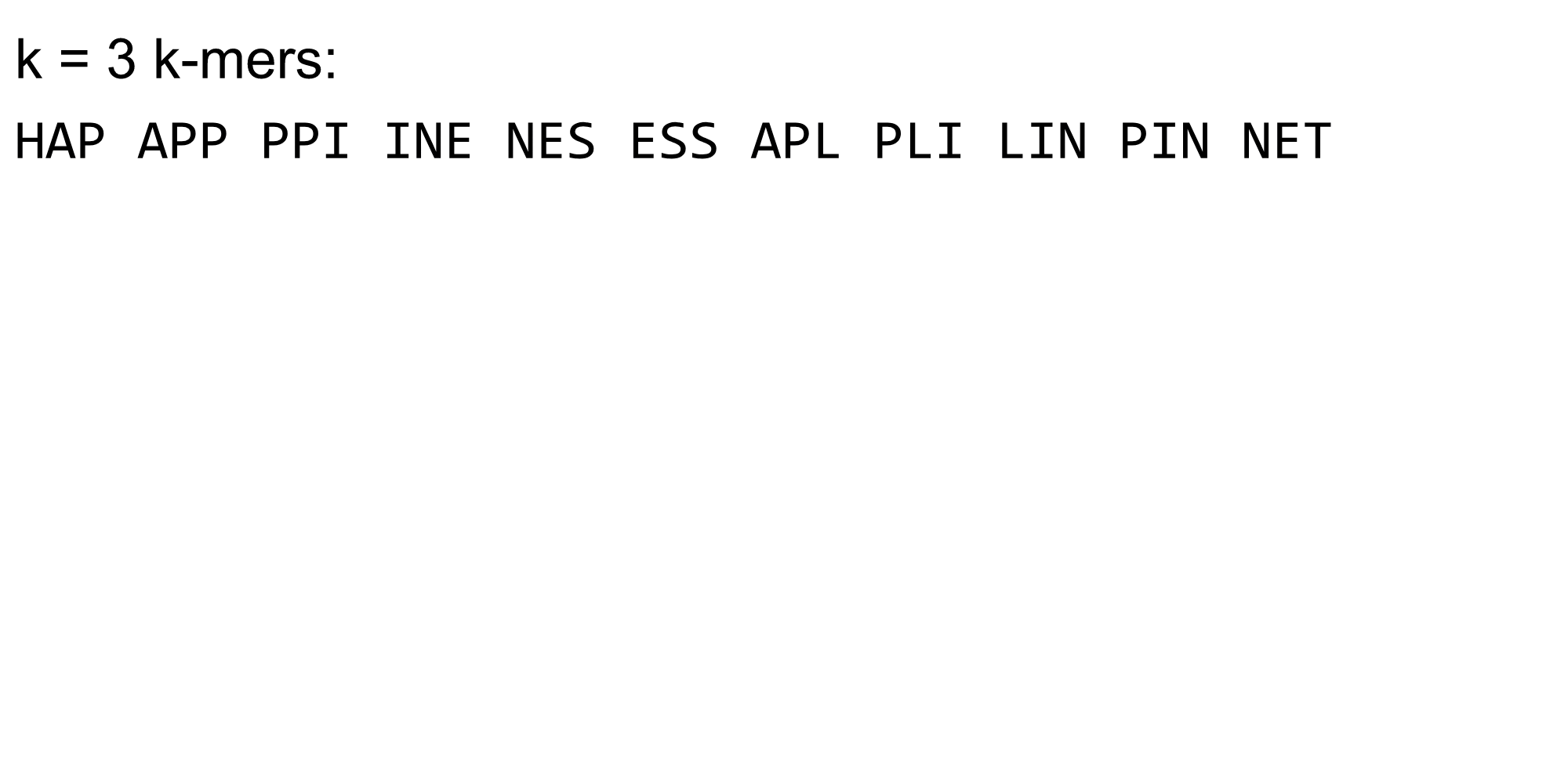

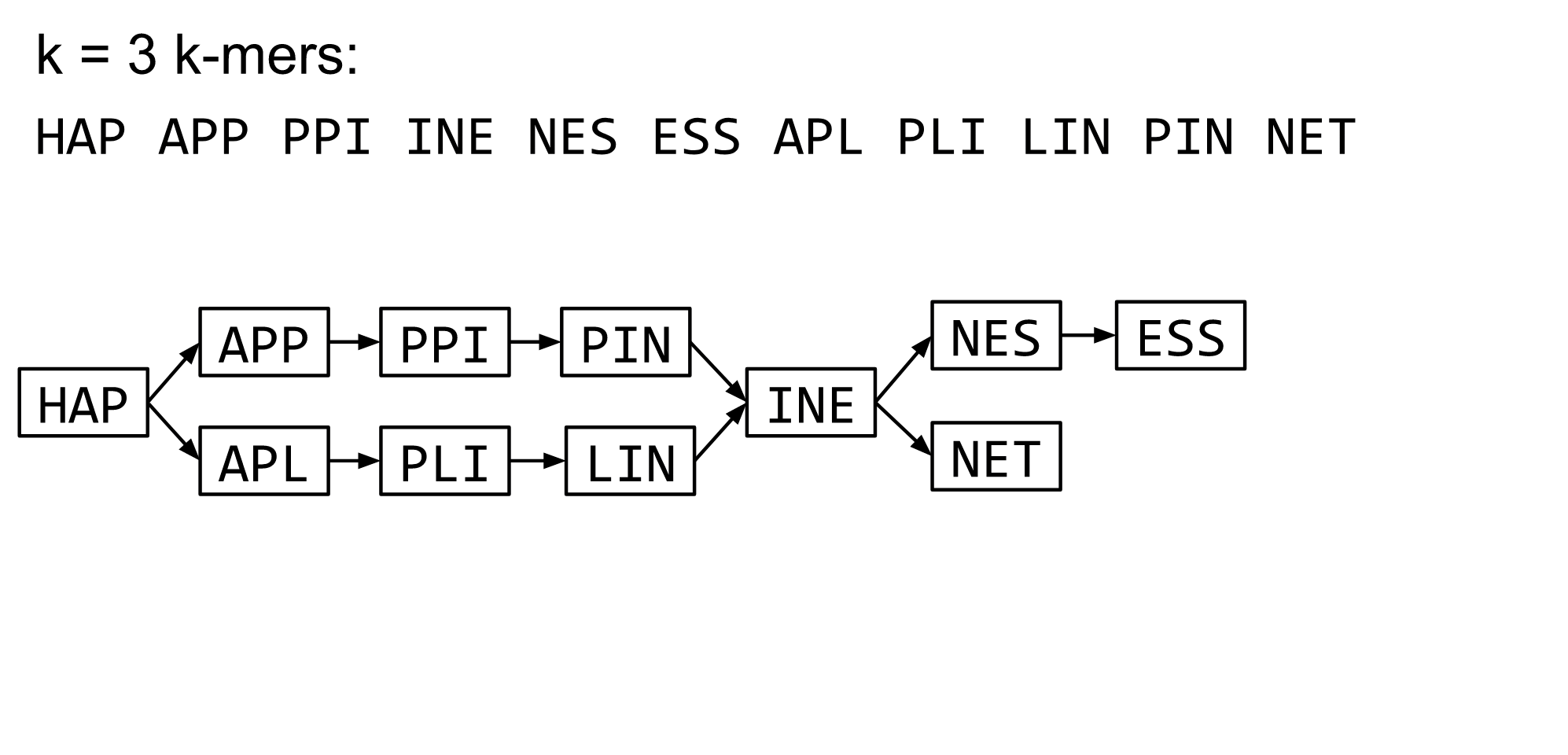

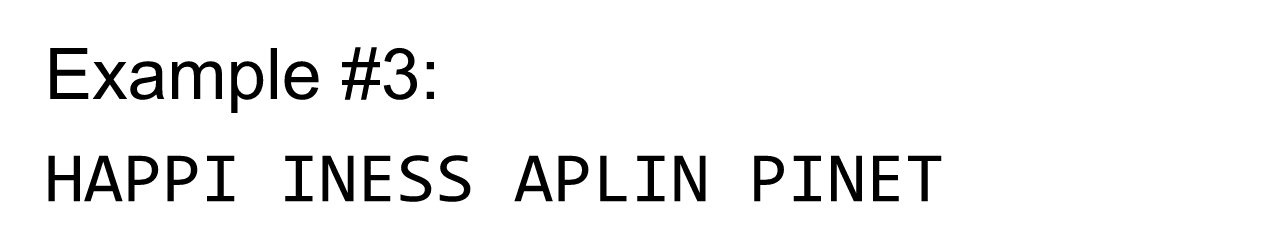

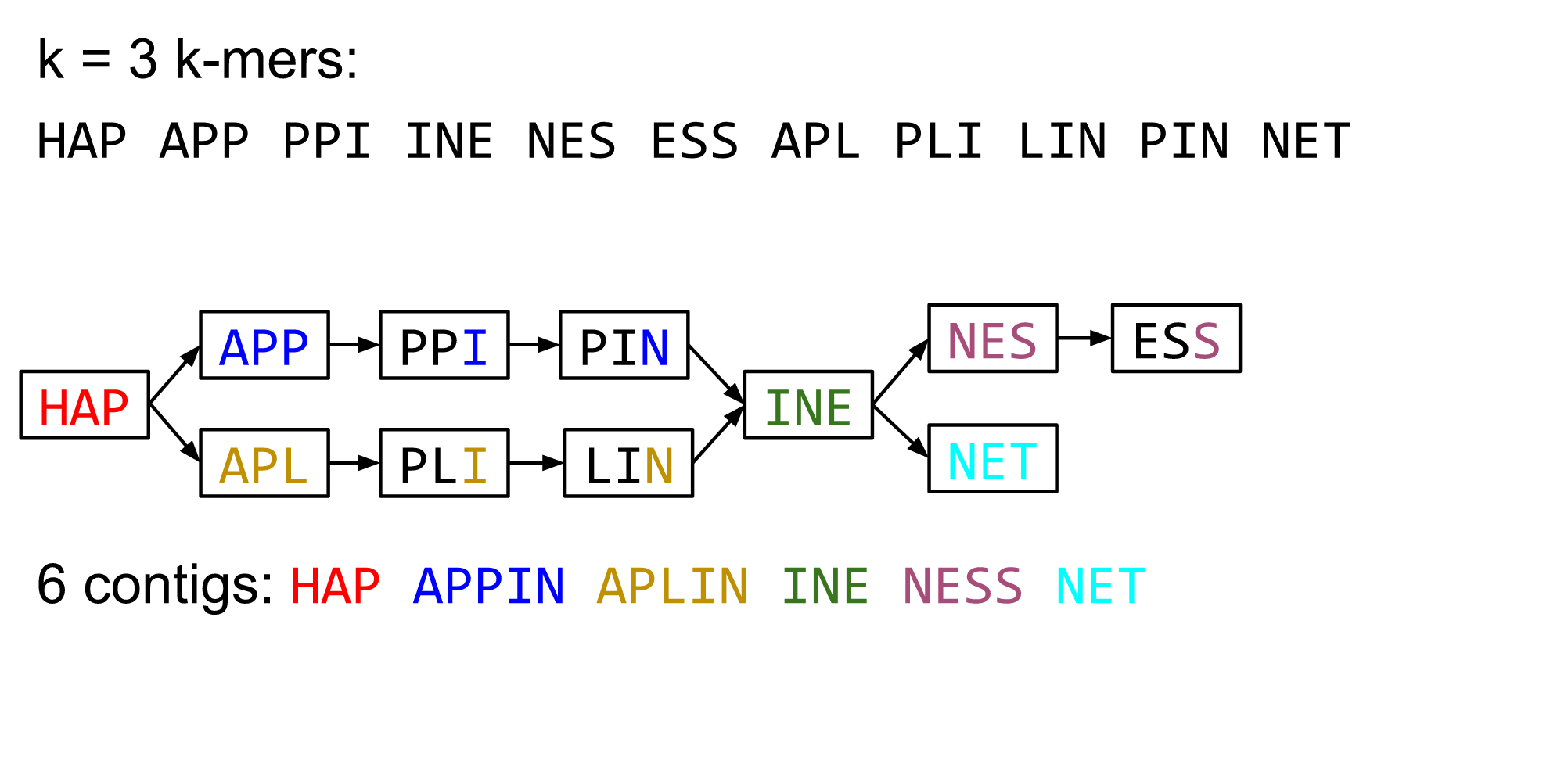

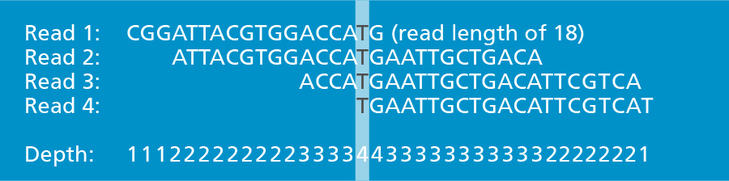

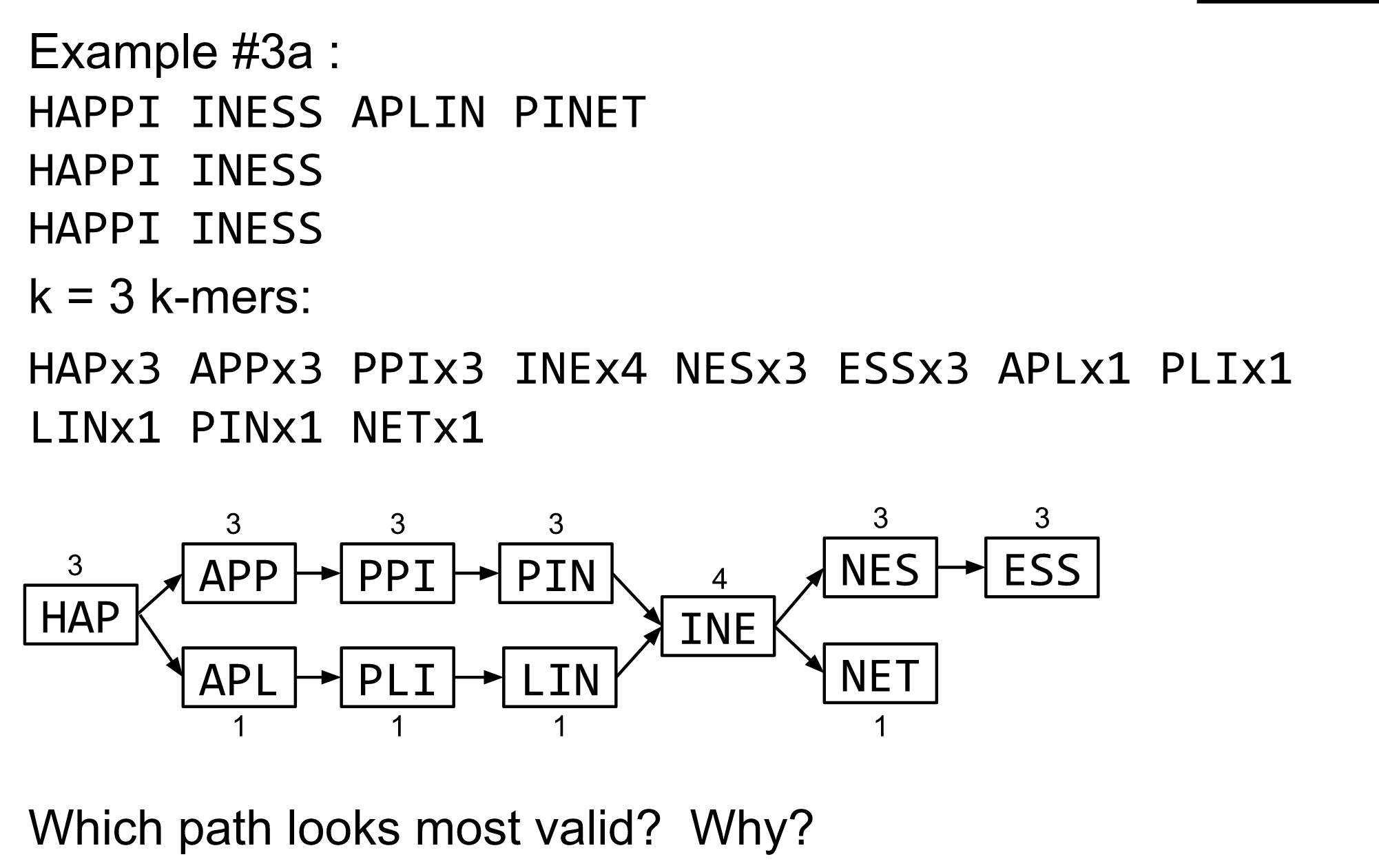

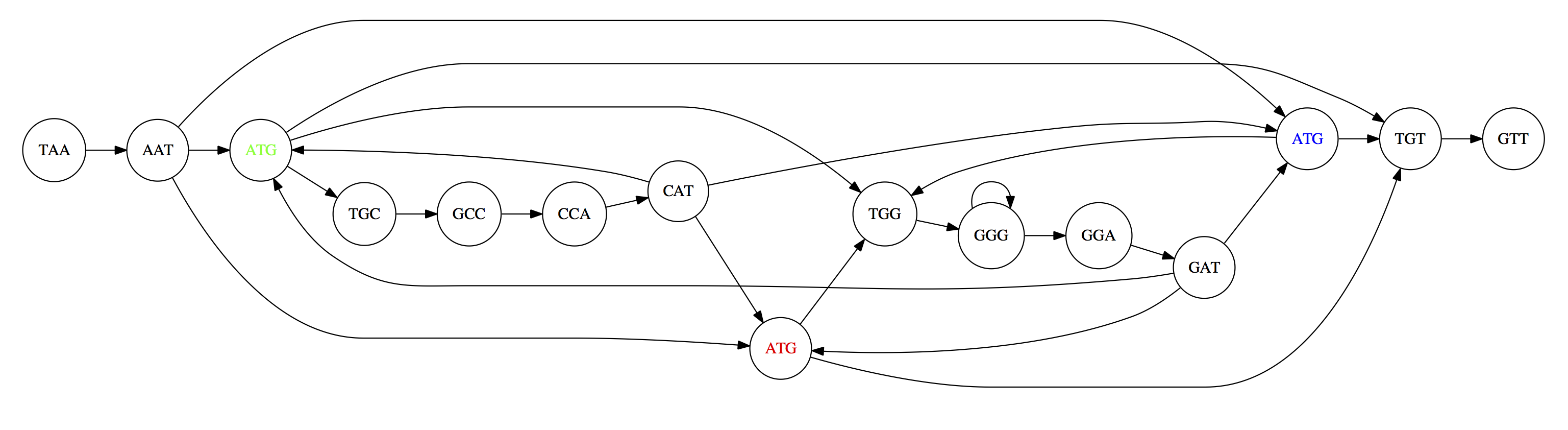

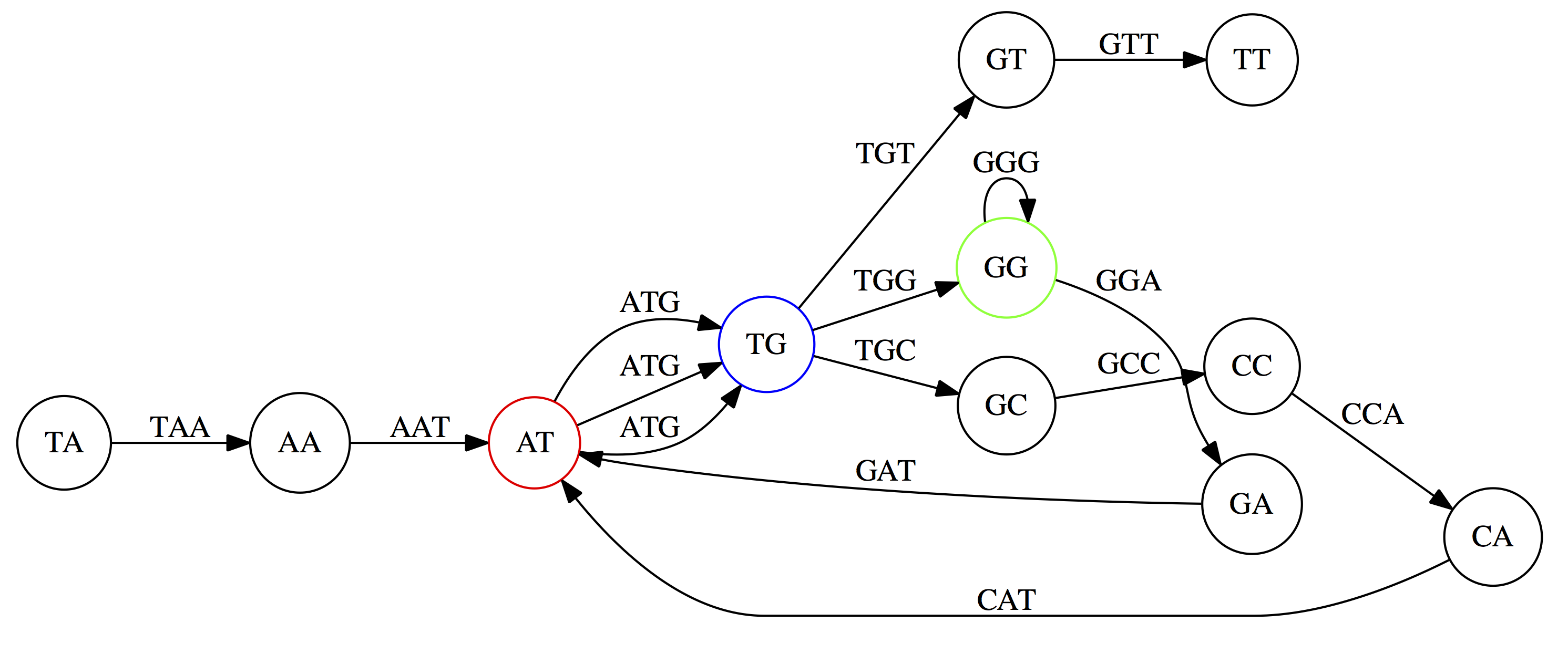

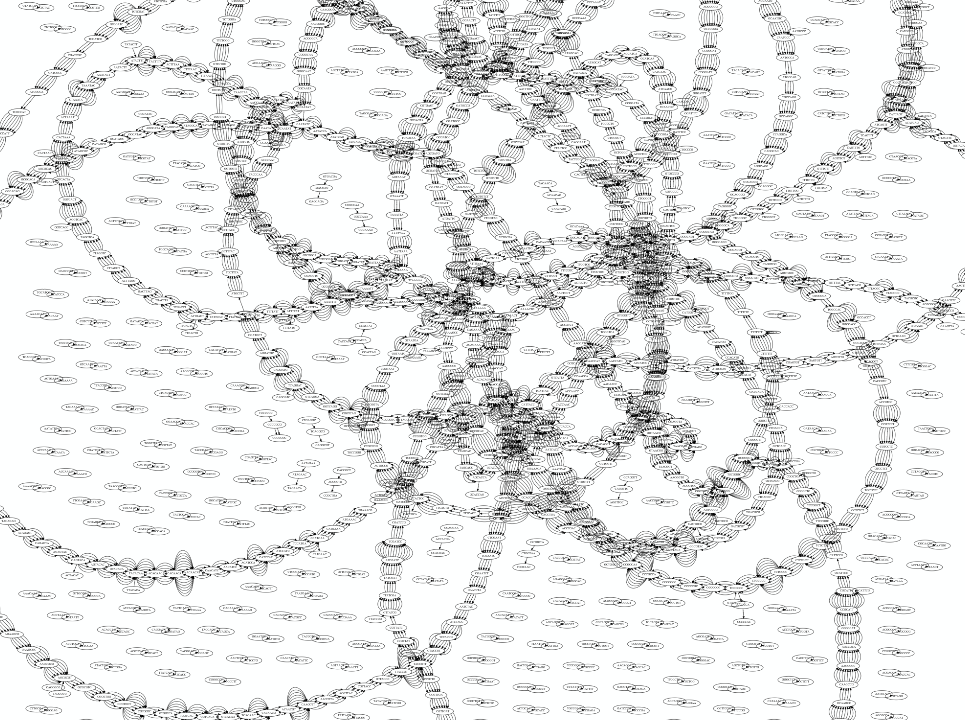

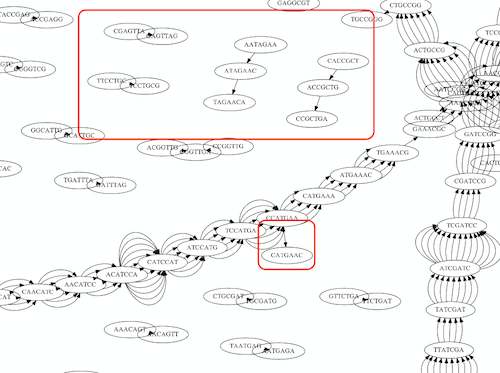

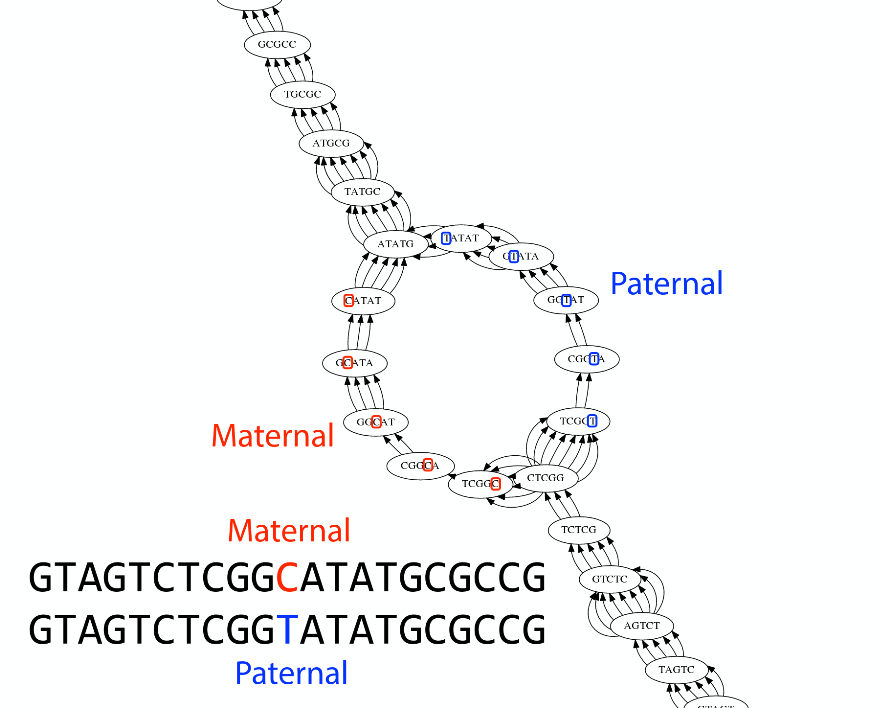

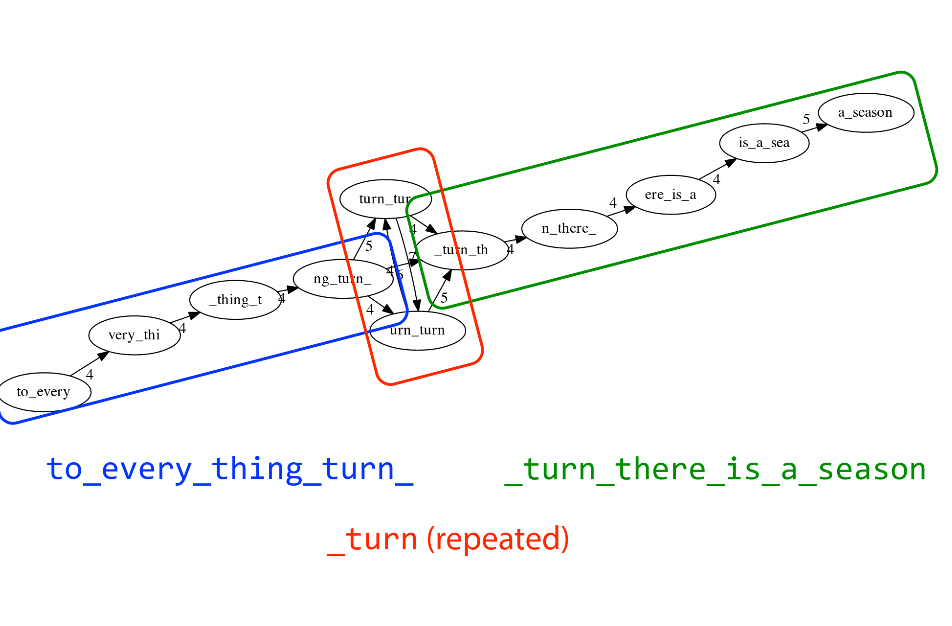

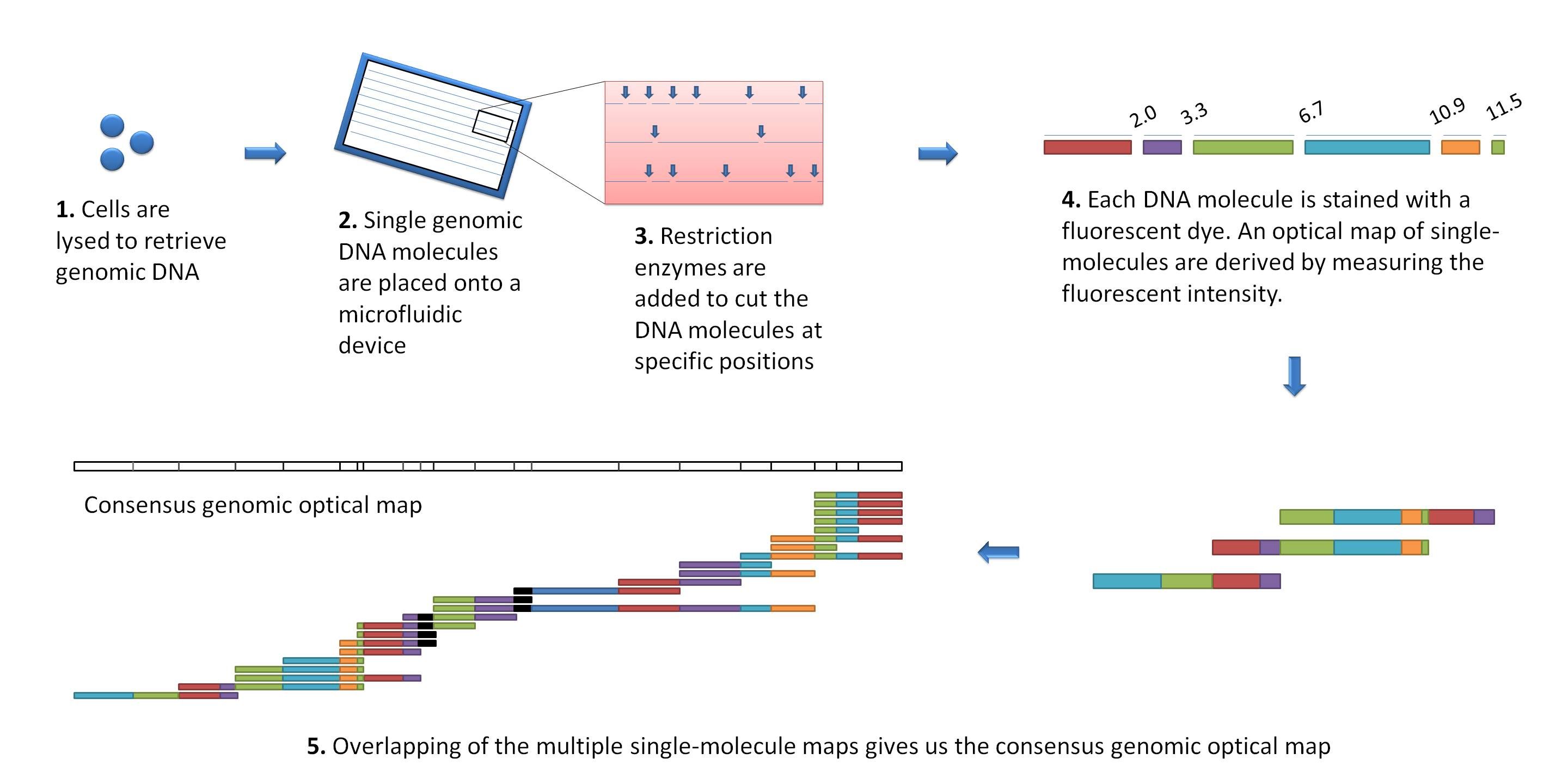

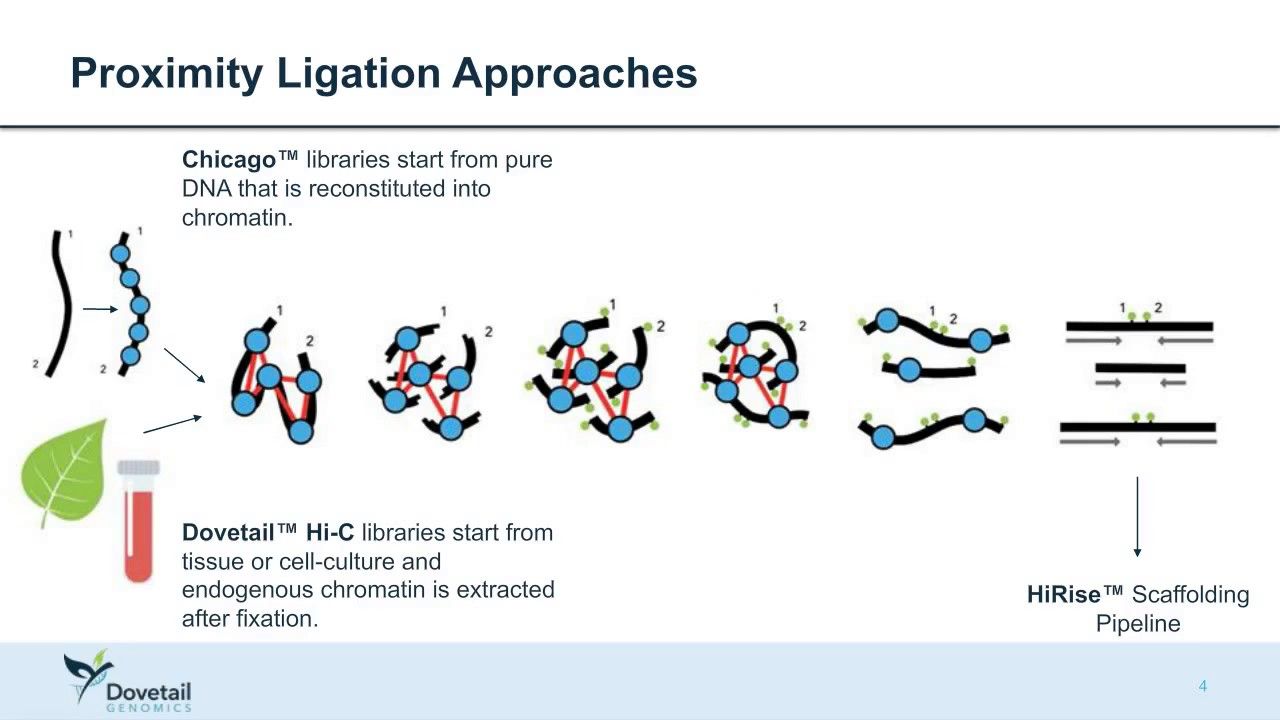

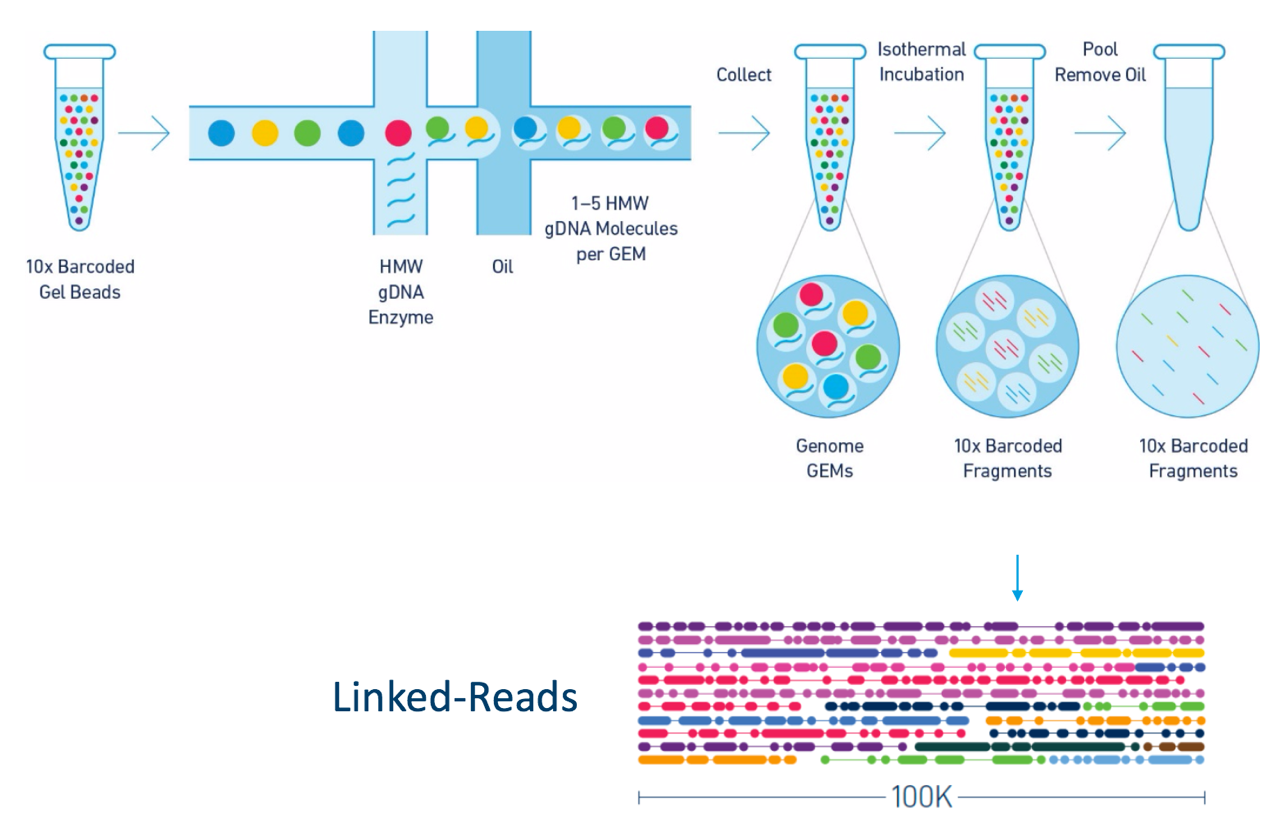

name: inverse layout: true class: center, middle, inverse <div class="my-header"><span> <a href="/training-material/topics/assembly" title="Return to topic page" ><i class="fa fa-level-up" aria-hidden="true"></i></a> <a class="nav-link" href="https://github.com/galaxyproject/training-material/edit/main/topics/assembly/tutorials/algorithms-introduction/slides.html"><i class="fa fa-pencil" aria-hidden="true"></i></a> </span></div> <div class="my-footer"><span> <img src="/training-material/assets/images/GTN-60px.png" alt="Galaxy Training Network" style="height: 40px;"/> </span></div> --- <img src="/training-material/assets/images/GTN.png" alt="Galaxy Training Network" class="cover-logo"/> # Deeper look into Genome Assembly algorithms <div markdown="0"> <div class="contributors-line"> Authors: <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/abretaud/" class="contributor-badge contributor-abretaud"><img src="/training-material/assets/images/orcid.png" alt="orcid logo"/><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/abretaud?s=27" alt="Avatar">Anthony Bretaudeau</a> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/slugger70/" class="contributor-badge contributor-slugger70"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/slugger70?s=27" alt="Avatar">Simon Gladman</a> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/nekrut/" class="contributor-badge contributor-nekrut"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/nekrut?s=27" alt="Avatar">Anton Nekrutenko</a> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/delphine-l/" class="contributor-badge contributor-delphine-l"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/delphine-l?s=27" alt="Avatar">Delphine Lariviere</a> </div> </div> <div class="footnote" style="bottom: 4 em;"><i class="far fa-calendar" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">last_modification</span> Updated: Dec 28, 2020</div> <div class="footnote" style="bottom: 2.5em;"><i class="fas fa-file-alt" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">text-document</span><a href="slides-plain.html"> Plain-text slides</a></div> <div class="footnote" style="bottom: 1em;"><strong>Tip: </strong>press <kbd>P</kbd> to view the presenter notes</div> ??? Presenter notes contain extra information which might be useful if you intend to use these slides for teaching. Press `P` again to switch presenter notes off Press `C` to create a new window where the same presentation will be displayed. This window is linked to the main window. Changing slides on one will cause the slide to change on the other. Useful when presenting. --- ## Requirements Before diving into this slide deck, we recommend you to have a look at: - [Introduction to Galaxy Analyses](/training-material/topics/introduction) - [Sequence analysis](/training-material/topics/sequence-analysis) - Quality Control: [<i class="fab fa-slideshare" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">slides</span> slides](/training-material/topics/sequence-analysis/tutorials/quality-control/slides.html) - [<i class="fas fa-laptop" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">tutorial</span> hands-on](/training-material/topics/sequence-analysis/tutorials/quality-control/tutorial.html) --- ### <i class="far fa-question-circle" aria-hidden="true"></i><span class="visually-hidden">question</span> Questions - What are the main types of assembly algorithms? - How do they perform with short and long reads? - How to improve assemblies using other technologies? --- # Different types of input data * Short reads (Illumina): numerous 👍, high quality 👍, cheap 👍, short 👎 * Long reads (PacBio, Nanopore): longer 👍, fewer 👎, (many) more errors 👎 Genome Assembly can be done with: * only short reads * only long reads * both (hybrid assembly) Specific algorithms for each --- # Genome Assembly algorithms Detect overlaps between reads to build the longest possible sequences Algorithms use graphs to represent overlapping reads/words Two steps: * Build a (huge) graph while reading the input data * Try to find the longest paths traversing the graph Two main types of algorithms: * Short reads: de Bruijn Graphs * Long reads: OLC (Overlap Layout Consensus) --- # OLC (Overlap Layout Consensus) The older, first used for Sanger sequencing Compare all reads, look for read overlaps If a *suffix* of one read is similar to a *prefix* of another read... ``` TCTATATCTCGGCTCTAGG <- read 1 ||||||| ||||||| TATCTCGACTCTAGGCC <- read 2 ``` ...then they may overlap within the genome. --- ## Directed graphs We build a *directed graph* where directed *edges* connect *nodes* representing overlapping reads:  >**Directed graph** representing overlapping reads. (Image from [Ben Langmead](http://www.cs.jhu.edu/~langmea/resources/lecture_notes/assembly_scs.pdf)). --- ## Directed graphs For example, consider these 15 three letter reads: TAA AAT ATG TGC GCC CCA CAT ATG TGG GGG GGA GAT ATG TGT GTT We're lucky, we know the corresponding genome sequence is TAATGCCATGGGATGTT So the 15 reads can be represented as the following directed graph:  --- **However**, in real life we do not know the actual genome! All we have is a collection of reads. Let's first build an overlap graph by connecting two 3-mers if suffix of one is equal to the prefix of the other: > > >**Overlap graph**. All possible overlap connections for our 3-mer collection. (Fig. 4.7 from [CP](http://bioinformaticsalgorithms.com/)) So to determine the sequence of the underlying genome we are looking for a path in this graph that visits every node (3-mer) once. Such path is called [Hamiltonian path](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamiltonian_path) and it may not be unique. --- For example for our 3-mer collection there are two possible Hamiltonian paths:   **Two Hamiltonian paths for the 15 3-mers**. Edges spelling "genomes" <code>TAATGCCATGGGATGTT</code> and <code>TAATGGGATGCCATGTT</code> are highlighted in black. (Fig. 4.9. from [[CP](http://bioinformaticsalgorithms.com/)](http://bioinformaticsalgorithms.com/)). --- The reason for this "duality" is the fact that we have a *repeat*: 3-mer <code>ATG</code> is present three times in our data (<font color="green">green</font>, <font color="red">red</font>, and <font color="blue">blue</font>). Repeats cause a lot of trouble in genome assembly. --- # Limits of OLC * Computationally intensive * Doesn't perform well with Illumina (massive amount of short reads) => deBruijn Graphs --- # **de Bruijn Graphs** Based on a counter-intuitive idea * Hash all reads in overlapping fixed-length words * Words = k-mers of size k * Build a directed graph where nodes are k-mers and edges represent overlaps between k-mers --- # **What are K-mers?**  --- # **K-mers de Bruijn graph**  --- # **K-mers de Bruijn graph**  --- # **K-mers de Bruijn graph**  --- # **K-mers de Bruijn graph**  --- # **The problem of repeats**  --- # **The problem of repeats**  --- # **The problem of repeats**  --- # **The problem of repeats**  --- # **Different k**  --- # **Different k**  --- # **Different k**  --- # **Different k**  --- # **Choose k wisely** * Lower k * More connections * Less chance of resolving small repeats * Higher k-mer coverage * Higher k * Less connections * More chance of resolving small repeats * Lower k-mer coverage ***Optimum value for k will balance these effects.*** --- # **Read errors** .image-75[]  --- # **Read errors** .image-75[]  --- # **Read errors** .image-75[]  --- # **Read errors** .image-75[]  --- # Coverage (or sequencing depth) The number of unique reads that contain a given nucleotide in the reconstructed sequence.  Source: [Wikimedia](https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Read,_read_length_and_read_depth_to_achieve_a_read_depth) **Estimated coverage** **(number of reads x read length)** / **estimated size of the genome** 1,000,000 reads x 150bp / 10Mb = **15X** --- # **More coverage** * Errors won't be duplicated in every read * Most reads will be error free * We can count the frequency of each k-mer * Annotate the graph with the frequencies * Use the frequency data to clean the de Bruijn graph ***More coverage depth will help overcome errors!*** --- # **Read errors revisited**  --- # **de Bruijn graph assembly process** 1. Select a value for k 2. "Hash" the reads (make the kmers) 3. Count the kmers 4. Make the de Bruijn graph 5. Perform graph simplification steps 6. Read off contigs from simplified graph --- # **Make contigs** * Find an unbalanced node in the graph * Follow the chain of nodes and "read off" the bases to produce the contigs * Where there is an ambiguous divergence/convergence, stop the current contig and start a new one. * Re-trace the reads through the contigs to help with repeat resolution --- # Assembly in real life In this topic we've learned about two ways of representing the relationship between reads derived from a genome we are trying to assemble: 1. **Overlap graphs** - nodes are reads, edges are overlaps between reads. 2. **De Bruijn graphs** - nodes are overlaps, edges are reads. --- # Overlap graph  --- # de Bruijn Graph - same data  --- Whatever the representation will be it will be messy:  A fragment of a very large De Bruijn graph (Image from [BL](https://github.com/BenLangmead/ads1-slides/blob/master/0580_asm__practice.pdf)). --- There are multiple reasons for such messiness: **Sequence errors** Sequencing machines do not give perfect data. This results in spurious deviations on the graph. Some sequencing technologies such as Oxford Nanopore have very high error rate of ~15%. > > >Graph components resulting from sequencing errors (Image from [BL](https://github.com/BenLangmead/ads1-slides/blob/master/0580_asm__practice.pdf)). --- **Ploidy** As we discussed earlier humans are diploid and there are multiple differences between maternal and paternal genomes. This creates "bubbles" on assembly graphs: > > >Bubbles due to a heterozygous site (Image from [BL](https://github.com/BenLangmead/ads1-slides/blob/master/0580_asm__practice.pdf)). --- **Repeats** As we've seen the third law of assembly is unbeatable. As a result some regions of the genome simply cannot be resolved and are reported in segments called *contigs*: > > >The following "genomic" segment will be reported in three pieces corresponding to regions flanking the repeat and repeat itself (Image from [BL](https://github.com/BenLangmead/ads1-slides/blob/master/0580_asm__practice.pdf)). --- # What to do with my reads? * Short reads => DBG assemblers (e.g. Spades, ABySS, DISCOVAR, Velvet, ...) * Long reads => OLC assemblers (e.g Canu, Falcon, Hgap4, ...) * Short + Long reads => hybrid assemblers (e.g. Unicycler, ...) Hybrid assembly: long reads to resolve repeats, short reads to correct errors Other data and tools for polishing (scaffolding, gap filling, ...) --- # Other data: Optical maps  (Source: [Wikimedia](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Optical_mapping#/media/File:Optical_mapping.jpg)) Use for scaffolding by comparing the restriction map with the predicted restriction sites in the contig sequences --- # Other data: Hi-C  (Source: Dovetail genomics) Sequence chunks of genome colocalized --- # Other data: Linked-Reads  (Source: 10X) Reads grouped by physical regions on the genome thanks to barcodes 10X Genomics (discontinued in 2020) --- ## Thank You! This material is the result of a collaborative work. Thanks to the [Galaxy Training Network](https://training.galaxyproject.org) and all the contributors! <div markdown="0"> <div class="contributors-line"> Authors: <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/abretaud/" class="contributor-badge contributor-abretaud"><img src="/training-material/assets/images/orcid.png" alt="orcid logo"/><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/abretaud?s=27" alt="Avatar">Anthony Bretaudeau</a> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/slugger70/" class="contributor-badge contributor-slugger70"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/slugger70?s=27" alt="Avatar">Simon Gladman</a> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/nekrut/" class="contributor-badge contributor-nekrut"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/nekrut?s=27" alt="Avatar">Anton Nekrutenko</a> <a href="/training-material/hall-of-fame/delphine-l/" class="contributor-badge contributor-delphine-l"><img src="https://avatars.githubusercontent.com/delphine-l?s=27" alt="Avatar">Delphine Lariviere</a> </div> </div> <div style="display: flex;flex-direction: row;align-items: center;justify-content: center;"> <img src="/training-material/assets/images/GTN.png" alt="Galaxy Training Network" style="height: 100px;"/> </div> <a rel="license" href="https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/"> This material is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License</a>.